When Rob Minnick needed money to fuel his betting habit, he often found it where a lot of gamblers do. He got a cash advance on a credit card.

Minnick was 18 years old when he started betting, convinced that his extensive knowledge of sports would make him a winner. The New Jersey native moved from daily fantasy sports to traditional sports betting to casino games. Eventually, he’d find himself sitting at an Atlantic City poker table while simultaneously peeking at his cell phone, where an online slot machine was spinning.

In late 2022, Minnick was in recovery from his gambling addiction when he had a relapse, which was fed by cash advances. It started with a sports bet, which led to a visit to Parx Casino in Bensalem, Pennsylvania.

By the time the 12-hour binge ended, it was close to midnight. Minnick had created so much debt that he says he had to work a second job for more than five months — and put all of his earnings into repayment — to dig out of the hole.

“With the credit cards, you know that the cash advance fee is going to be huge,” Minnick said. “And you don’t care. Because you’re convinced that you’re going to win it back.”

Over the last six years, legal gambling has spread like a weed across the United States. In early 2018, before a pivotal U.S. Supreme Court decision, only Nevada allowed sports wagering. Now 37 states, plus the District of Columbia, do. State lawmakers have moved quickly amid fears that standing pat will result in a loss of tax revenue as their residents gamble in neighboring states.

Pro sports leagues — once hostile to gambling due to fears that the integrity of their games could be compromised — have embraced the financial opportunities that gambling offers. A year ago, the first-ever sportsbook inside an NFL stadium opened at FedEx Field in suburban Maryland. And fans watching on TV are now inundated with gambling ads.

The ease of access to legal gambling has also soared, as bettors increasingly place their wagers on mobile apps, which is feeding fears that a problem-gambling epidemic is building. In 28 states, gamblers can make sports wagers from their mobile phones, according to the American Gaming Association.

At least six more states currently allow online casino games. As online gambling’s legal status has changed, so has the stance taken by many U.S. banks. Just a few years ago, the mainstream financial industry wanted nothing to do with online wagering, which generally involved offshore operations of dubious legality.

Today, gambling is a growing source of revenue for banks.

“The opportunities for them are overshadowing the risks and dangers,” said Brianne Doura-Schawohl, a lobbyist who advocates for policy responses to problem gambling.

But judging by the experiences of the United Kingdom, which has a longer history of widespread legal gambling than the United States, banks here may eventually be dragged into the burgeoning debate over how to address problem gambling.

After all, banks provide credit to bettors who have already depleted their savings. Banks are also well positioned to offer ways to make it easier for problem gamblers to protect themselves from their own self-destructive impulses. And banks hold reams of transaction data that can indicate which customers have gambling problems.

Back when legal gambling in the U.S. was happening only in casinos, and bettors needed to use cash, banks had less information about who might have a gambling disorder. That’s changed in the era of online betting.

But what is the proper role for U.S. banks in addressing problem gambling? So far, there has been little public discussion of that question. And there are no easy answers, as Minnick’s experiences illustrate.

“There was always a way to spend more money than I had when I was gambling,” said Minnick, who has been in recovery since his November 2022 relapse. “And that was even without the use of credit cards.”

Of course, specific banks can decide to ban the use of plastic to fund their customers’ gambling accounts. But cash advances offer a simple way around such restrictions, since they don’t trigger a gambling-related merchant category code. Another workaround: using a credit card to purchase a gift card or e-wallet funds.

“I can broadly say that people who are addicted to gambling develop the ability very, very rapidly to get money that they don’t have when they need it,” Minnick said.

There is also the politically charged question of how to balance harm reduction with personal autonomy.

“There’s no clear-cut solution right now that everyone would be happy with,” Minnick said.

Minnick, who will turn 25 in February, now creates content on TikTok, Instagram and YouTube in an effort to help people with gambling problems. He goes by the name Rob Odaat, which is recovery-speak for “one day at a time.” In a recent interview, he was self-reflective about the factors that fueled his addiction.

“I’m responsible for all the things that I did, and I made my life continuously more difficult to live,” he said, before noting that the next stage of his escalating problem — such as his move from sports betting to casino games — was always easy to find in the gambling apps he used.

“They put it one click away,” he said. “And it’s always very obvious where it is on the screen.”

Like others who are trying to help problem gamblers, Minnick sees an analogy between the current moment and the early days of the opioid epidemic, when addicts were often stigmatized.

“I think that over the next eight years, it’s going to go through the full cycle that opioid addiction went through,” he said.

Kyle Massi

‘Responsible’ vs. ‘safer’ gambling

Gambling in the U.S. is regulated at the state level. And to the extent that state laws deal with addiction, it’s typically by establishing hotlines that gamblers may call if they believe they have a problem. This approach has led to gambling ads that end with narrators rattling off various states’ hotline numbers at breakneck speed.

Gambling operators also offer voluntary tools designed to limit the compulsive behavior of players who recognize they have a problem. For example, the sports betting site FanDuel allows its users to put limits on the amount of money they can deposit in their accounts

during a given period of time. FanDuel users can also cap the size of any wager, as well as the number of hours they can spend on the site each day. Or they can exclude themselves from gambling on FanDuel altogether.

The umbrella term that’s used to describe the dominant U.S. approach to staving off the harms caused by addictive behavior is “responsible gambling.” The basic idea is to provide tools and resources to help bettors manage their time and money while gambling. Gamblers, according to this school of thought, ultimately have responsibility for their own behavior.

Supporters of this philosophy say that it’s in keeping with the American ethos of self-reliance.

“Especially in the U.S., people don’t like to be forced to do anything,” said Joseph Watkins, president of World-Pay Gaming Solutions.

Critics of the responsible gambling approach argue that it’s ineffective. Kasra Ghaharian, a senior research fellow at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas’s International Gaming Institute, said that tools that allow people to block their own participation in gambling have low uptake rates.

“All these tools are great, but no one uses them,” he said.

The United Kingdom, by contrast, is taking a more heavy-handed stance, which is generally known as “safer gambling.”

In a white paper released last April, the U.K. Gambling Commission proposed a system of “financial risk checks” for gamblers who breach certain loss thresholds. The goal is to assess whether the gambler can afford to lose the money that he or she is wagering.

Under the U.K. commission’s proposal, relatively basic checks would be conducted on bettors who record a net loss of 125 pounds in a month or 500 pounds in a year at a particular gambling operator. The operators would conduct the checks, which would look at factors such as court judgments, bankruptcies and the average affluence within the gambler’s postal code.

“These checks should take seconds to process and would be frictionless for the consumer,” the Gambling Commission stated in its white paper, titled “High Stakes: Gambling Reform for the Digital Age.” “We estimate only around 20% of accounts in a calendar year will trigger this check as most never lose this much gambling.”

The commission also proposed more intrusive checks — which would provide more insight into the gambler’s discretionary income — in cases where net losses exceed 1,000 pounds in a rolling 24-hour period. “Such rapid losses are highly unusual and exceed the discretionary income nearly all people likely have available for a day’s activity, so are therefore highly indicative of risk,” the commission stated.

Still to be determined is exactly how these more detailed financial risk checks — also known as affordability checks — would be conducted. The Gambling Commission said that it expects most of the checks could be done by contacting credit reporting agencies, which would provide an estimate of the gambler’s overall disposable income. In some cases, the individual gambler might have to provide information, but the Gambling Commission stated that it might be possible to streamline the process using open banking.

“The Commission is currently working with the financial services sector to explore how more detailed checks would work in practice,” the white paper stated.

Also up in the air, for now, is what exactly U.K. gambling operators would be expected to do with the information they gather. The white paper contemplates a range of possible responses, including applying limits to specific accounts and ending customer relationships in situations that raise serious concerns.

The proposed affordability checks have sparked controversy. Nevin Truesdale, CEO of The Jockey Club, a U.K. horse racing organization, has launched a petition against them. “We believe such checks — which could include assessing whether people are ‘at risk of harm’ based on their postcode or job title — are inappropriate and discriminatory,” Truesdale has argued.

But Lucy Frazer, a Conservative member of Parliament who serves as the U.K. government’s culture secretary, has defended the commission’s proposal. The Gambling Commission estimates that roughly 300,000 people in Great Britain are experiencing problem gambling, and that another 1.8 million individuals are gambling at elevated levels of risk.

All told, those 2.1 million people account for about 3% of the country’s population.

“This government is not in the business of telling people how they can and can’t spend their money,” Frazer wrote in an op-ed late last year. “But we know, for some, gambling leads to a dangerous cycle of addiction that can feel impossible to escape. We have a duty of care to those at the greatest risk of devastating and life-changing financial losses.”

‘The final destination before you’re done’

Not every response to problem gambling in the U.K. relies on government intervention.

For instance, the Premier League, the world’s top professional soccer league, has voluntarily agreed to remove gambling sponsorships from the front of players’ jerseys by the end of the 2025-2026 season, in an effort to reduce gambling’s appeal to kids.

Last April, when the Premier League announced the new policy, eight of the league’s 20 teams had gambling sponsorships on the front of players’ shirts. Numerous U.K. banks, meanwhile, offer features that allow gamblers to block themselves from betting at all, rather than using the self-exclusion features on multiple gambling apps. Those banking-app features, which have yet to gain steam at stateside banks, will typically decline any gambling transactions for three days, providing a cooling-off period to habitual gamblers who want to walk away. HSBC UK is one of the banks that offers such a tool.

“The 72-hour restriction aims to help give our customers time to pause when they are tempted to return to gambling,” Maxine Pritchard, head of financial inclusion and vulnerability at HSBC UK, said in an email.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, some U.S. states have taken a harder line than others on the use of credit cards. Iowa is one of a handful of states that — like the United Kingdom — bans the use of plastic in online sports betting.

“Credit is credit. And gambling has its addiction side,” said state Sen. Tony Bisignano, who was an architect of Iowa’s online sports gambling legislation. “If you mesh the two together, at some point someone will gamble their future away.”

Bisignano, a Democrat, said he believes that Iowa’s ban on the use of credit cards in gambling has saved lives.

“I think credit is the final destination before you’re done,” he said.

Some major U.S. credit card companies are taking a less restrictive stance. A JPMorgan Chase spokesperson said that the bank permits betting transactions where they are legal. Wells Fargo allows its credit cards to be used for lawful purposes, according to a spokesperson.

Bank of America, on the other hand, does not allow credit card transactions with gambling-related merchants, according to a company spokesperson. Citigroup declined to comment.

To advocates concerned about gambling addiction, banning the use of credit cards is a no-brainer. “Playing with money you don’t have can be a red flag,” said Doura-Schawohl, the lobbyist who advocates for policy responses to problem gambling.

Even without putting blanket bans in place, there are steps that credit card issuers could take to protect customers who show signs of having a gambling problem, said Les Bernal, national director of Stop Predatory Gambling, a nonprofit advocacy network.

Bernal would like banks to alert their customers when credit card transaction records indicate that the cardholder is chasing gambling losses, or continuing to place bets in an effort to make up for losing wagers. After all, banks have a unique vantage point that gives them a detailed picture of their customers’ gambling activity.

Those automated messages might work similarly to the fraud protection alerts that cardholders receive when they travel to a different city and make an unexpected purchase. “That was me, I wanted to make that transaction,” Bernal explained.

But the compulsive nature of gambling addiction could limit the effectiveness of this strategy; gambling addicts in the midst of a binge may not be receptive to an intervention from their bank.

Jon-Pierre Micucci, a recovering gambling addict who lives in San Francisco, recalled that he sometimes got phone calls from his bank’s fraud protection department in response to his online gambling sessions. While stuck at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, Micucci fell under the spell of online slot machines operated by unlicensed offshore companies.

“They would offer to hide the transactions like a porn site does. So it would show up as, like, Tommy’s Jeans from Indonesia,” said Micucci, who is now project manager of problem gambling hotlines at Health Resources in Action, a nonprofit consulting organization.

Micucci recalled that his bank statement might have shown roughly 150 consecutive transactions, all in the same odd amount. “All international, all sketchy,” he said.

But when his bank called Micucci to ask about the transactions, he would say: “It’s okay. Those are international. I accept those. And then I was off and running. They would never stop me again.”

Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg

‘Bet now/pay later’

The large buy now/pay later firms Klarna and Affirm have not embraced legal gambling. But a nascent product from an upstart competitor specifically targets bettors. Its design has sparked concern that it could feed gambling addictions.

The product, Edge Boost, is being billed as “the first bet now/pay later program for sports bets.” It will allow users to double the size of their wagers, using borrowed funds that they can repay at 0% interest in four weekly installments.

Edge Markets, the company that offers Edge Boost, expects to earn money from interchange fees. It will also charge fees to users who make an early repayment in order to regain access to their full borrowing capacity, according to a promotional video for the product.

“Let’s say you’re feeling great about this weekend’s game, but wish you had an extra $100 to wager,” says the video’s narrator. “Double down, and double your winnings.”

That message, which overlooks the possibility that the gambler will lose the bet, has generated outrage among problem gambling advocates. “This platform glorifies and entices people to spend more than they can afford to lose,” Doura-Schawohl told a sports betting publication last year.

Seni Thomas, the founder and CEO of Edge Markets, said that Edge Boost is in a testing phase, working with Cross River Bank and Galileo Financial Technologies, which is owned by SoFi Technologies. He is looking to launch the product in the first half of 2024, and he said it would be available in 27 states.

A Cross River spokesperson confirmed the New Jersey bank’s involvement. A SoFi spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

Thomas has a response to criticism of his company’s product. He argues that Edge Boost will serve as a replacement for illegal gambling, saying that many people bet in the black market because their bookies give them an advance, which is generally not available from regulated companies.

“Bookies want you to lose, and then they start charging interest on the balance,” Thomas said.

He also opined that there’s a misconception that people who gamble are degenerates: “I think people have watched too many movies, frankly.

“These are people that are quite sophisticated,” Thomas added. “They have the cash to back it up — high-income earners.”

It’s true that a majority of gamblers are not addicts.

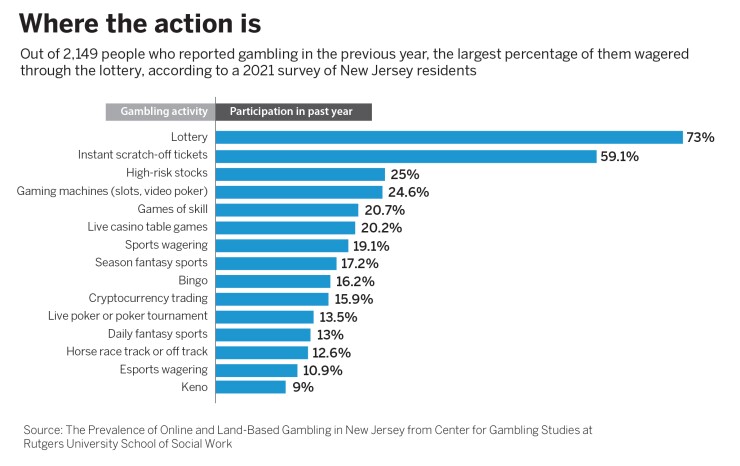

Last year, researchers at the Center for Gambling Studies at Rutgers University published the results of a phone survey of 3,512 New Jersey residents. Although roughly 61% of the respondents had gambled in the last year, just under 6% of the respondents were classified as “high-risk problem gamblers.” Another 13% of the participants reported low to moderate gambling problems.

Those numbers suggest that a clear majority of gamblers place wagers as a form of entertainment, and they don’t bet more than they can afford to lose.

The Rutgers research also found that the prevalence of high-risk problem gamblers in New Jersey — a state that has a long history of legal casino gambling — was about three times higher than the average rate in a majority of population surveys both domestically and abroad.

Minnick, the gambling addict who has been in recovery since relapsing in November 2022, grew up in Washington Township, New Jersey, less than an hour from Atlantic City. Today he expresses the clear perspective of someone who’s been through recovery. He says that the archetypal gambling addict has an internal desire to accomplish great things, but without putting in a lot of effort.

When he was betting, Minnick once accumulated enough rewards points with Caesars Entertainment to receive a free three-day trip to the Bahamas, where Caesars had a partnership with the Atlantis resort and casino. He was flattered. He felt important.

In the early stages of the trip, Minnick’s wagers weren’t paying off. He decided to place a sports bet, known as a parlay, that would pay out if six different games ended the way he’d predicted.

Minnick correctly forecast the first five legs of the bet. The last contest was a regular-season NBA game between the New York Knicks and the Minnesota Timberwolves.

Minnick had put his money on the Knicks, who held a big lead in the second half. The parlay included a feature that would have allowed Minnick to cash out early for roughly 95% of the value of the win. But he refused to budge. The Timberwolves came back and won the game 102-101.

“I lost the bet, and I spiraled and spent even more money on credit in the casino,” Minnick recalled. “So what started out as feeling like a great gambler, a great big shot, turns into feelings of greed. It turns into feelings of depression.

“But it always came down to this belief that it would be different the next time,” he explained. “I would figure it out, and I’d come out on top. And you just don’t.”

One way that Minnick found the money he needed for gambling was by exploiting the fact that U.S. banks didn’t typically settle transactions over the weekend. It’s a loophole that could be closed if real-time payments gain widespread adoption.

Minnick explained, as a hypothetical example, that he might have had $500 in his bank account on a Friday. He would deposit the $500 into the sportsbook. Then he would wager away all $500. “Most people would say, ‘Okay, I have zero dollars, so I can’t gamble.’ But the bank doesn’t process that transaction until Monday. So between Friday and Monday morning, the bank sees that you have $500 in your account,” Minnick said.

Before the weekend was over, Minnick would move another $500 into his account at the sportsbook. “And the banks don’t catch it until Monday morning,” he explained.

“If you’re addicted to gambling, you’ll say something like, ‘Okay, I’m down $1,000 now, which means I’m going to have a $500 overdraft. So now I need to pull out another $1,000,” Minnick said, adding that gamblers convince themselves that they’ll win enough money to pay back the overdraft fees they’ve incurred. “And you dig yourself such deep holes because the bank catches up on Monday.”

‘It’s about putting as many barriers in place’

Gambling industry insiders argue that the rise of legal online betting in the U.S. has brought significant advantages compared with the status quo prior to April 2018. That’s when the Supreme Court opened the floodgates by striking down a federal law that had barred most states from legalizing sports wagering.

First, people in the gambling industry point out, plenty of Americans were making illegal online bets prior to 2018. Legalization has allowed for regulation and oversight, and it’s enabled states to collect tax revenue. Electronic payments also offer various advantages over the paper currency that long ruled Las Vegas.

One asset of noncash payments is that they generate customer-specific data, which can be used to identify problem gamblers and help bettors set and stick to budgets. And data can be harnessed to provide customers with visual signals — such as green, yellow and red lights — about when it’s safe to gamble.

“We can guide people to a certain behavior without forcing them,” said Omar Sattar, co-founder and CEO of Sightline Payments, which specializes in serving the gambling industry.

Ghaharian, the senior research fellow at UNLV, wrote his doctoral dissertation about how payments transaction data can be used to identify markers of gambling-related harm.

Analyzing gambling payments data from more than 2,200 online casino players, he found three clusters of customers whose behavior indicated they were at potential risk of harm, including a group that had high decline rates even though their deposit amounts were low. “That might be a little bit of a red flag,” Ghaharian said.

Ghaharian recently got access to a new dataset, which he hopes will reveal patterns about how gambling transactions relate to other kinds of payments. One goal of the research is to look at how markers of financial vulnerability — or the ability to withstand a financial shock — relate to gambling spending.

Even some people in the gambling industry say that more needs to be done to address problem gambling. Jonathan Michaels, who consults for gambling firms on payments issues, said there needs to be further collaboration between financial institutions and gambling operators in order to determine when problematic behavior is occurring. “The industry hasn’t taken true proactive approaches,” he said in reference to both banks and gambling companies.

But skeptics wonder whether the gambling industry will ever take aggressive action, given its heavy reliance on frequent gamblers as a source of revenue. The states, which collect taxes from gambling, arguably have a similar conflict of interest.

According to that logic, the financial sector is the one major player that doesn’t have a vested interest in maximizing gambling revenue. Matt Zarb-Cousin, the U.K.-based co-founder of Gamban, which offers gambling blocking software that’s designed to be difficult to remove, described financial institutions as a disinterested third party.

He argued that there is no one silver-bullet solution in the battle against gambling addiction: “It’s about putting as many barriers in place.”

There’s no shortage of recommendations for how banks can contribute. Stop Predatory Gambling suggests not only larger ideas like credit card bans, but also smaller ones. For example, the banking industry could promote one day a year, similar to National No Smoking Day, when Americans are encouraged not to gamble.

Banks could also throw their support behind the idea that all gambling apps and slot machines must have a warning that reads, “The money that I’m gambling is not borrowed, and I can afford to lose it.”

Gambling reform advocates have generated at least two other ideas for how banks could help. One is to communicate with young people and vulnerable populations about problem gambling.

Banks could also take steps to help their customers understand how much they’ve spent each month on wagers. “It isn’t their problem to solve,” Zarb-Cousin said.

“But they are in a very good position to solve it,” he added.