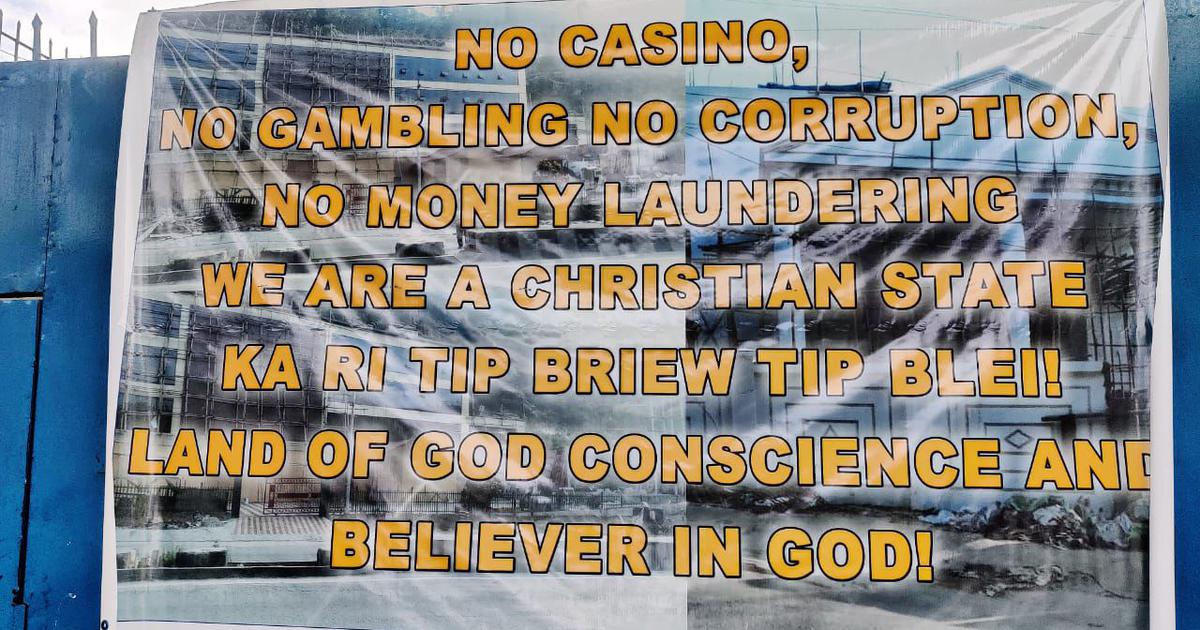

The state government’s move to legalise and regulate certain forms of gambling in Meghalaya has been met with fierce resistance.

The government argues opening casinos would boost tourism, which is facing competition from other North Eastern states, and earn revenue. This has not gone down well in predominantly Christian Meghalaya, where public opinion is often shaped by powerful tribal organisations such as the Hynniewtrep Youth Council as well as by church groups.

Trouble started when the government passed the Meghalaya Regulation of Gaming Act in 2021, which appeared to reverse the state’s decades-old ban on most forms of gambling. Opposition parties, including the Trinamool Congress, joined the Hynniewtrep Youth Council and various church groups in demanding the repeal of the new law.

“We are opposing the act from the religious and morality point of view,” said Hynniewtrep Youth Council general secretary Roy Kupar Synrem. “Meghalaya being a Christian state, we don’t want activities like casinos and gambling. The youths will be addicted to gambling and we don’t want those kinds of activities and environment in the state.”

Given the opposition, the government seemed to pull the brakes on implementing the law. A fresh furore broke out last month when the government told the state assembly that temporary licences had been issued to three firms in March. Chief Minister Conrad Sangma then gave assurances that the government had ordered a halt on all processes to start casinos after it held talks with church groups and non-governmental organisations. The temporary licences, issued before the talks, would “lapse automatically”, he claimed.

However, pressure groups want the gambling law to be scrapped altogether.

Games of chance and skill

Till last year, the Meghalaya Prevention of Gambling Act, 1970, had prohibited most forms of gaming in the state. The new law aimed to introduce licences and regulation for “games of skill”, where a player’s skill determines the game rather than luck, such as bridge, backgammon, poker and bingo. It also sought to regulate “games of chance”, where luck mattered over skill, such as baccarat, roulette and the three card game. Both online and offline games are mentioned.

What the new law does not mention is “teer”, a game of archery where the players place bets on the number of arrows that stick to the target at the end of each round. The practice of betting on archery contests is believed to date back to the early 20th century. The state is dotted with thousands of such teer gambling parlours, with about 1,500 in the capital of Shillong itself.

Till 1981, teer gambling was banned. Since then, it has been regulated by the Meghalaya Amusements and Betting Tax (Amendment) Act, 1982, and conducted under the aegis of the Khasi Hills Archery Sport Association. In 2018, the government introduced the Meghalaya Regulation of the Game of Arrow. Shooting and the Sale of Teer Tickets Act, 2018.

Those who oppose the new gambling law do not object to teer, arguing that the game has deep cultural roots in the Khasi community, combining art, entertainment and skill.

“Archery is not harmful, it is a sport,” said EH Kharkongor, secretary of the Khasi Jaintia Christian Leaders Forum.

Synrem also agreed teer was a traditional betting game which could not be compared to casinos where lakhs and crores could be lost and won.

‘High price to society’

The anxieties about casinos are outlined in a letter sent by the Khasi Jaintia Christian Leaders Forum to the chief, demanding the repeal of the new gambling law as it came “with a high price to the society”.

“The legitimisation of gambling is detrimental to the society as it has negative effects on quality of life such as loss of self-esteem, breakdown in relationships, depression and even suicides and fatal self-inflictions,” the letter said. “Gambling can increase criminality in several ways such as forgery, fraud, robbery and murder to finance one’s gambling habit.”

Kharkongor told Scroll.in that they opposed the law because it would enable all forms of gambling, not just the games mentioned in the law. “The introduction of casinos will affect so many dimensions of human lives and communities,” he said. “It will promote violence, drugs related incidents, flesh-trade and violent crimes and so many other immoral and criminal activities.”

Synrem complained the government had not consulted stakeholders before introducing the new gambling law.

Generating revenue?

As the controversy blew up last month, Sangma argued in the state assembly that the new law would only help regulate gambling. He claimed the rules said “locals cannot play”.

“Hence, we thought that we should have gaming zones which are far away from the core of the state and capital in areas which are at the border areas so that our people are nowhere close to it. We thought it was a win-win situation for the state,” the chief minister said in the assembly.

He also suggested the aim behind setting up casinos was to generate Rs 500-600 crore in revenue at a time when other sources of revenue, especially mining, had dried up.

The Hynniewtrep Youth Council was not convinced. Synrem pointed out that the 2021 act only said that licensees had to ensure a player – anyone taking part in a game online or on physical premises – was above 18 years old.

“[It] speaks of nothing when it comes to participation of local youths or residents of the state in online Gaming or betting,” he said.

The Hynniewtrep Youth Council dashed off a letter to the chief minister saying, “If the state government can check the revenue leakages as has been repeatedly pointed out and flagged by the CAG Reports every year, it can easily save about Rs 1500-2000 crore annually.”

Kyrsoibor Pyrtuh of Thma U Rangli Juki, a civil society organisation, also said it was unlikely to help Meghalaya’s economy since most investors were likely to be from outside the state.

Trinamool Congress legislator George B Lyngdoh also spoke at protests asking for a repeal of the law altogether, not just a halt on casinos. “Everyone possesses cellphones and has the power in their hands to participate in online betting and gambling, which will lead to addiction even though they do not go to casinos,” Lyngdoh said. “They would play at home, at educational institutions.”