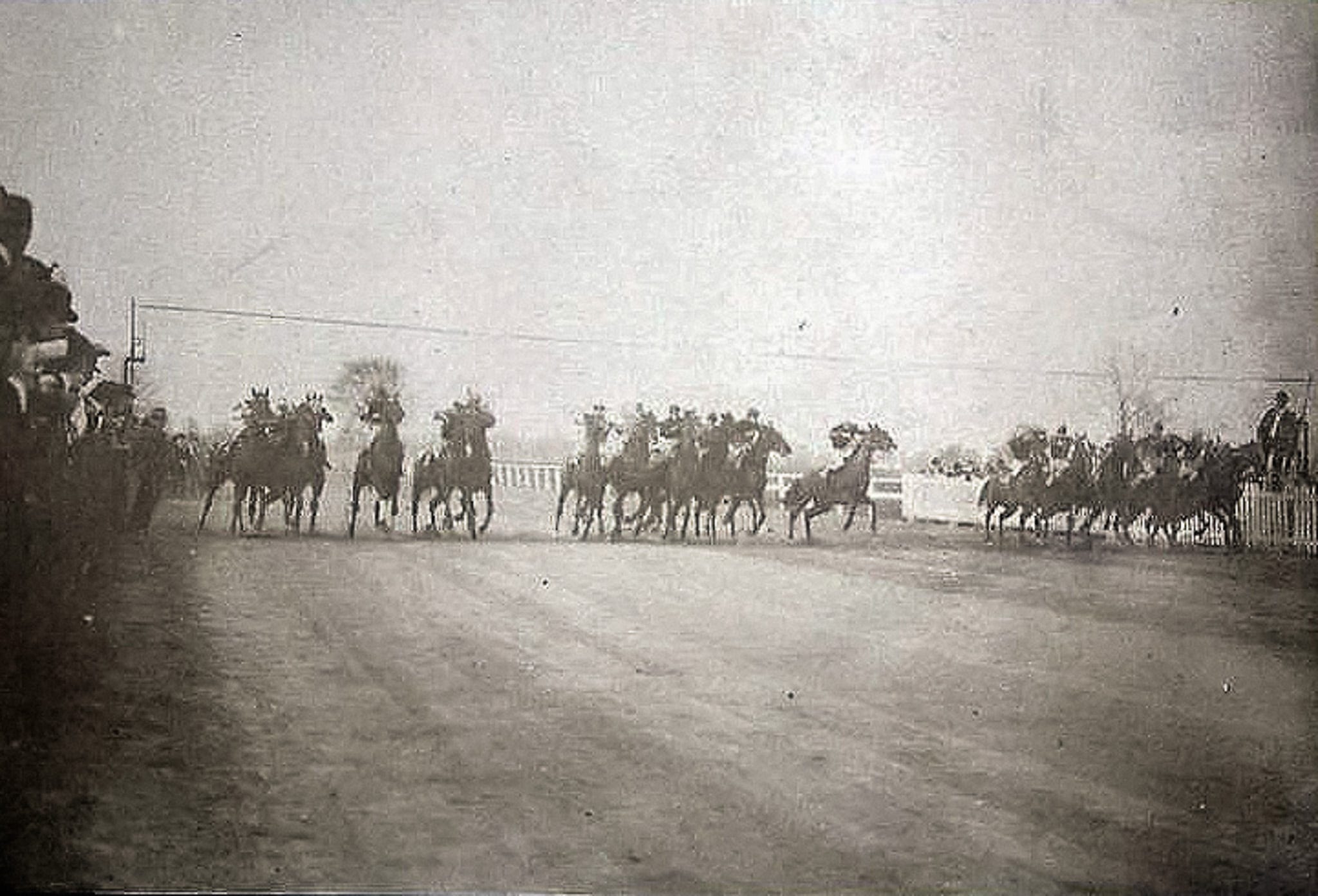

The spectators came to Memphis’ Montgomery Park on April 24, 1906, from Arkansas, Mississippi, Kentucky, and surrounding towns. “They besieged the ticket windows and entrance gates,” wrote the Commercial Appeal, “eager to be on time for the Tennessee Derby.”

In the stands, the state’s elite gathered, said the Commercial Appeal, “to witness the thoroughbreds battle for the rich plums and purses.” The track at Montgomery Park, named for New Memphis Jockey Club founder Henry A. Montgomery, was the equal of those in Louisville, Chicago, and Saratoga Springs, New York, locals boasted.

By custom on Derby Day, which Memphis celebrated like a holiday each April, the infield was open free of charge to all. Black residents of the city showed up early for a spot along the fence. Many of the jockeys were also Black, and the best enjoyed national fame despite the growing grip of Jim Crow.

The mile-and-a-furlong Tennessee Derby was “the first important race of the season in this country,” according to the New York Times.

That day a chestnut filly named Lady Navarre, after driving hard down the final stretch, won the race trailed a length by Good Luck, a favorite. Riding Lady Navarre was Thomas H. Burns, a Canadian jockey who 77 years later would be inducted into the U.S. Racing Hall of Fame.

No one that April day in Memphis could have guessed they were watching the last Tennessee Derby.

The Tennessee legislature put an end to gambling in the state the following winter, which also ended the Tennessee Derby.

Today, the Kentucky Derby, which runs this year on May 6, is when most Americans briefly turn their attention to the ponies. The race at Louisville’s Churchill Downs launches the Triple Crown. Once upon a time, though, the “sport of kings” was America’s pastime, and the Tennessee Derby was a race the whole country followed.

How horse racing won over the South

On December 5, 1752, the first important thoroughbred race on American soil took place near Williamsburg, Virginia. Five horses completed the four-mile course, and a mare born in England took the prize.

Horse racing became a favorite pastime of the colonial elite. It was a way to prove their sophistication by embracing a sport patronized by English royalty. It also let them signal their wealth.

“An expensive thoroughbred, the Mercedes-Benz of the 18th century, was an emblem of wealth and status and a proud extension of his owner,” wrote historian Randy J. Sparks.

From the start, horse racing in America had critics. The devout did not like the gambling. The revolutionaries disapproved of its aristocratic air. The American Revolution put a damper on American horse racing.

The races slowly resumed after independence. The opulence of the sport fit the ambition of Southern plantation owners. Charleston became the center of racing in the young country.

Tennessee had thoroughbreds even before it became a state in 1796, and by 1839 the state had 10 tracks and 37 stallions at stud, more than Kentucky according to a 1947 article in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly. Most thoroughbreds were raised in Middle Tennessee, which had the same nourishing bluegrass as Kentucky. Belle Meade outside Nashville became a world famous stud farm.

“The prevailing opinion in the South is that Tennessee possesses more and better blood than Kentucky. Tennessee stock will fetch more money in the South than ours will,” said a prominent Kentucky breeder in 1836.

As tension rose between the two regions with the approach of the Civil War, “sectional races” were held that pitted a Northern horse against a Southern one.

The Civil War devastated Southern horse breeding. The wealthy white planters could no longer afford the sport, and the rising industrialists and bankers in the North were eager to invest. And during the fighting, Union troops “foraged” for horses, often pressing prized racers into military service.

The brief life of the Tennessee Derby

In 1836, the wealthy businessman Henry A. Montgomery founded the New Memphis Jockey Club. By the middle of the century, it bought land for a track, on the site where the Memphis Fairgrounds sits today. And with the Tennessee Derby, which first ran in 1884, the club had a race that became talked about nationwide.

In the early years, crowds could be sparse for the Tennessee Derby and the other races, especially if they fell when cotton needed to be harvested. But it was soon Memphis’ biggest event, attracting thousands.

“The race course is a democratic ground. Men, women and children are there from every walk of life,” reported the Memphis Appeal in 1889. “They jostle one against another in the greatest good humor. The man who wins is a hero for half an hour. He who loses finds it best to jest with those who jest at him.”

The first three years, 1884 to 1886, the Tennessee Derby, like the Kentucky Derby a race for 3-year-old thoroughbreds, was a mile and half. The derby itself was not held from 1887 to 1889, although other races took place those years. When it returned the length was shortened to one and an eighth miles.

The Tennessee Derby was known “to be one of the many defeats for favorites,” according to the Chicago Tribune, frequently crowning horses who entered the race with odds against them.

As the 20th century began, forces were again aligned against horse racing in the United States. The religious still opposed gambling, and in the South they had power. The growing progressive movement, which would become an official party in 1912 under Theodore Roosevelt, also was not fond of the ponies.

“Not only is horse racing seen as promoting organized crime, which is terrible, but it’s also making life difficult for working class families, who spend too much time at the track gambling away family money,” said racing historian Steven A. Reiss.

The Jockey Club in Memphis, however, was not worried — even after an anti-gambling bill was introduced in the Tennessee legislature at the start of 1907. The recently elected governor, who won with the support of the wealthy horse owners, was a lifelong member of the Memphis Jockey Club and “never pretended to see all evil in the sport,” wrote The Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky.

Despite the turfmen’s confidence in their power to sway state politicians to their position, gambling in the state of Tennessee was banned.

The Jockey Club considered holding the race without gambling, which would have caused them to likely lose $30,000 to $40,000, around $1 million adjusted for inflation. They looked at buying nearby land in Arkansas or Mississippi to build a new track. They even talked to New Orleans about hosting the Tennessee Derby and other major races that year.

In the end, thoroughbreds did not race that year nor any year since in Tennessee. By 1910, the last horses at Montgomery Park were sent to other stables and for the first time in 50 years no thoroughbreds wintered in Memphis.

The anti-gambling fervor would also end racing in other places, if only temporarily. Bookmaking was even banned in Kentucky, but a loophole was found to allow parimutuel betting and the Kentucky Derby was saved.

Will racing ever return?

Marshall Gramm, an economics professor at Rhodes College, owns nearly 100 thoroughbreds with partner Clay Sanders and other investors. They call their partnership Ten Strike Racing, in honor of the horse who won the first Tennessee Derby. But all of their horses are stabled outside Tennessee, in Arkansas, Kentucky, Pennsylvania and New York.

“I would be shocked if there are more than 20 thoroughbreds bred a year in Tennessee,” Gramm said. “My guess is it’s a byproduct of breeders who have the facilities for the Tennessee Walkers.”

The docile Tennessee Walker, originally called a Plantation Horse, became popular in the mid-20th century.

The only major race in the state is Nashville’s Iroquois Steeplechase, which is run by a nonprofit and does not allow gambling.

Efforts have been made to bring back thoroughbred racing to Tennessee. The most recent attempt was a bill introduced in 2019 that failed to gain traction. For a time in the late 1980s and 1990s, a window was open for a new Tennessee horse track, but none of the proposals had the financial backing to win state approval. Eventually in 1998 the Racing Commission was disbanded, and the law that created it was repealed in 2015.

Gramm noted that betting on horses has been less popular in recent years, as lotteries and sports betting have become legal in more states. The tracks also take a large cut of any winning bet, up to 20%, which makes wagering on other sports more appealing.

Michael Kisber and his son Zachary are also Memphis-based owners of thoroughbreds. Michael Kisber’s dad taught him to bet the ponies. Zachary Kisber got his first taste of racing when he was 10 years old during a trip to Universal Studios in Southern California when the family detoured to the track at Santa Anita Park.

“I just fell in love with the sport, the beauty of the horses, all of the strategy,” Zachary Kisber said.

Like Gramm, the Kisbers are part of a small group of racehorse owners in Tennessee. They have had success at the Breeders’ Cup and in Dubai.

“We run it like a business and treat it like a business,” said Michael Kisber. “But you don’t get into it to make a profit.”

The Kisbers are also attached to the history of racing in Tennessee. Their jockey silks are inspired by a 1908 lapel pin from the Memphis Jockey Club.

They do not, however, have much hope that thoroughbred racing will ever return to Tennessee. The biggest impediment, they said, is that most U.S. racetracks rely on an attached casino to turn a profit.

“Tennessee is not going to approve casino gambling,” Michael Kisber said. “I don’t think racing is ever coming back. It would be too much.”

Todd A. Price covers culture in the South. He can be reached at [email protected].