The NCAA Division 1 Men’s Basketball Tournament, which just got underway, is the pinnacle of college sports, an annual all-American rah-rah celebration of athletic competition. The Big Dance. The Final Four. March Madness!

It is also, increasingly, a chance for a lot of people to bet a lot of money.

From the casual fun of picking brackets for an office pool, the tournament has evolved to become “America’s most wagered-on competition,” according to the American Gaming Association, an industry group, surpassing even the Super Bowl in numbers of bets placed. This year the AGA expects the college hoops contest will attract $15.5 billion in bets from 68 million Americans, a huge increase from last year when the group estimated 45 million people would bet $3.1 billion. The driving force behind that stunning five-fold jump, the AGA says: the growing popularity of legal online sports betting.

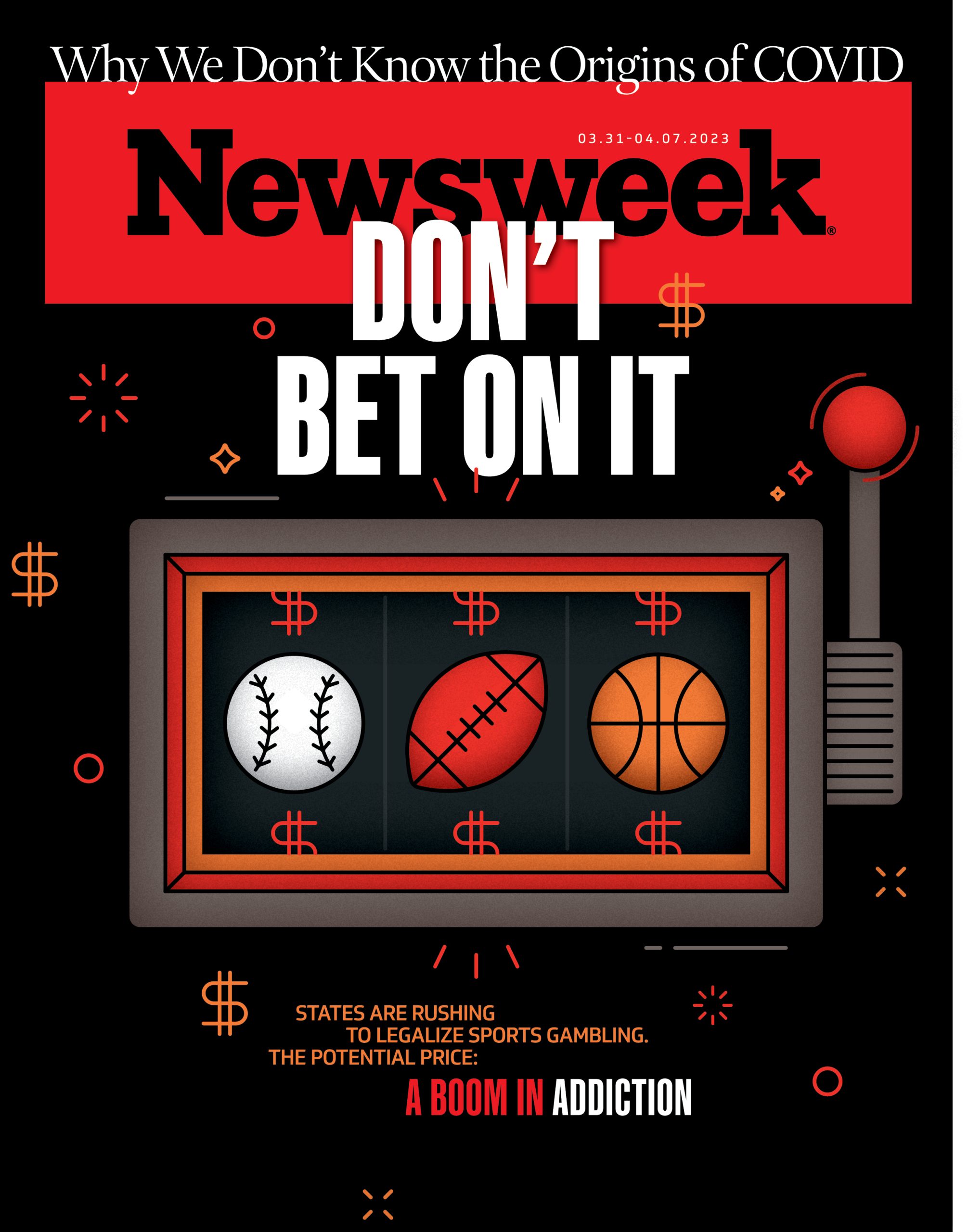

Since a Supreme Court ruling opened the door in 2018, legal sports betting has exploded in the U.S., fueled by easy access through online apps and expensive, star-studded ad campaigns for online sportsbooks. Some 36 states have passed laws to allow gambling on sports, another eight are considering it and more than half of American adults—146 million people—now live in a live, legal sports-betting market. The result: record-breaking revenue for the betting companies, a tax windfall for states and a sharp and troubling rise in serious gambling problems and addiction. It’s a trend that experts believe may rapidly worsen, given what is known about the trajectory of compulsive gambling and the experience of countries that have had legal sports betting in place far longer than the U.S.

Calls to gambling helplines reflect the growing problem. In 2021 (the most recent year for which data is available), calls to the helpline run by the National Council on Problem Gambling, a gaming industry supported group, rose 43 percent, while texts increased 59 percent and chats jumped 84 percent. That’s troubling, but a Newsweek analysis of the available data in every state that has legalized sports gambling since the Supreme Court ruling shows an even more dramatic spike in pleas for help. In Connecticut, for example, helpline calls jumped 91 percent in the first year after legalization; in Massachusetts, calls are up 276 percent since 2020; in Ohio, which just opened the door to legal sports betting in January, calls to the state’s problem gambling hotline tripled in the first month alone compared to the same period last year; in the first year after Virginia legalized sports gambling, calls climbed 387 percent; in Illinois, calls rose 425 percent between 2020 and 2022.

Especially troubling to experts: The fastest-growing group of sports bettors—and the ones who seem to be getting into the most trouble—are typically people in their twenties, spurred by easy access on their phones and ubiquitous advertising. Young men, who are the main target audience for sports betting companies, are the most vulnerable. “We believe that the risks for gambling addiction overall have grown 30 percent from 2018 to 2021, with the risk concentrated among young males 18 to 24 who are sports bettors,” said Keith Whyte, executive director of the National Council on Problem Gambling, in an interview with Pew Research last year.

Getty

The physiology of young adults, who are still a work in developmental progress, adds to the risk that sports betting will become problematic for them. Says Pamela Brenner-Davis, team leader of the New York Council on Problem Gambling, “Young people, particularly those under the age of 25, still have underdeveloped brains that make them predisposed to addiction, particularly to gambling addiction.”

The problems that can often result—getting into debt, rifts in relationships, difficulty holding down a job—are serious, as is the impact on emotional well-being. Lia Nower, director of the Center for Gambling Studies at Rutgers University School of Social Work, says, “The more people gamble, the more activities they gamble on, and the younger they start, the more likely they are to develop problems with not only gambling itself but also mental health problems like depression, anxiety and suicidality.”

“I doubt folks really understand the pervasiveness of it,” Anne McCollister of Nebraska’s Gamblers’ Assistance Program says.

Your Brain on Sports Betting

For many people, of course, gambling is just fun, and not every wager on basketball, the Super Bowl or a Premier League match leads to a compulsive habit. But for others it can turn into an addiction just like dependency on tobacco, alcohol or opioids. Studies have found gambling activates a reward system in the brain in the same ways substance addictions do and problem gambling is similar to those addictions in clinical expression, brain origin, comorbidity, physiology and treatment.

“The strongest component of the addiction of smoking, drugs or alcohol—not the only one, but the strongest one—is debatably dopamine,” says psychologist James Whelan, director of The Institute for Gambling Education and Research at the University of Memphis. “And when you gamble, your brain secretes more dopamine than when you do any of those other things.”

The latest edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual lists “gambling disorder” in the same category as heroin and opioid addictions. The criteria for the diagnosis include the need “to gamble with increasing amounts of money to achieve the desired excitement,” “repeated unsuccessful attempts to control, cut back or stop gambling,” jeopardizing or losing a “significant relationship, job or educational or career opportunity due to gambling” and relying on others “to provide money to relieve desperate financial conditions caused by gambling.” Some studies have found that as many as 19 percent of problem gamblers attempt suicide, the highest rate of any addiction.

Betting on sports comes with its own unique set of risks. Many sports bettors tend to see their wagers as safer and more informed than other kinds of gambling, researchers say; they think they know the game, the players and the teams, and are being guided by their own expertise and skill rather than luck. This may give them an illusion of control over the outcome. That can lead to more problems when a bet goes bad. According to one study in the journal Addictive Behaviors, “Sports betting, relative to non-sports betting, has been more strongly linked to gambling problems and cognitive distortions related to illusion of control, probability control and interpretive control.”

Chris Graythen/Getty

Sportsbooks lean in on those emotions, particularly among more vulnerable young men, advertising heavily on university campuses, with whom some have made sponsorship deals. Their flashy advertising features cool movie and sports stars—Jamie Foxx, Kevin Hart, J.B. Smoove, Drew Brees, the Manning family and many more—and promotes the idea that picking winners in sports is a matter of skill not luck. BIA Consulting estimates that the total nationwide advertising spend on sports betting will be close to $1.8 billion this year.

The ad frenzy is being driven not just by the size of the sports betting market but also by what gambling industry analysts expect to be an eventual shakeout that will leave just a few big winners. The many sportsbooks in operation now are racing to grab market share before that happens and their strategies to add new bettors add to the risk that wagering may get out of control. The companies run promotions like offering free bets and boosted odds. They also compete to offer the widest variety of bets, including “prop bets,” side wagers on things other than the outcome of a game, like a player’s total assists. Some companies also offer in-play betting, wagers made during the heat of a game when the bettor’s emotions are likely to be high and ability to manage risk low. Plenty of excitement and a range of potential bets is never further than your cell phone.

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg/Getty

New Jersey as Ground Zero

The road to the current state of legal sports gambling in the U.S. started in the Garden State. Prior to the Supreme Court ruling, a 1992 federal law, the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, (PASPA) made most sports betting illegal anywhere but Las Vegas. The law, sponsored by then New Jersey Senator Bill Bradley, a former Princeton University and New York Knicks basketball star, was designed to stop the potential spread of legal sports betting. Proponents said it would help keep sports honest by shielding them from point-shaving and game fixing. Opponents said it would just drive gambling more firmly under the control of organized crime.

Bradley notwithstanding, however, there had long been support for legal gambling in New Jersey. In 1974, Atlantic City had become the first American city outside of Nevada with legal casinos. In 2011 New Jersey voters approved legalizing sports gambling in a referendum, and in 2012 Governor Chris Christie signed a legal sports betting bill into law. The NCAA, the National Football League, Major League Baseball, the National Basketball Association and the National Hockey League all sued the state in federal court to block the law, invoking PASPA. The state lost, but eventually appealed to the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, the atmosphere around sports betting had shifted considerably. Many states were interested in the idea. The gaming industry, of course, supported this and was throwing lots of lobbying money around. Even the sports leagues that had been officially opposed to any kind of gambling since the 1919 Black Sox scandal had changed their minds. In 2014, NBA commissioner Adam Silver wrote an op-ed for The New York Times saying the time had come to legalize sports betting, provided regulation included things like measures to prevent underage gambling and to provide help for people with gambling problems.

In May 2018, the Court found for New Jersey, concluding that PASPA was unconstitutional; Congress had no business telling states they couldn’t have legal gambling if they wanted it.

The first legal sports bet in New Jersey was made only a month after the Supreme Court decision and it wasn’t long before problem gambling began to tick up. In fiscal 2019, 606 calls were made to the state’s gambling helpline. By fiscal 2021, that had more than doubled to 1,439. According to Rutgers University’s Center for Gambling Studies, which tracks betting in the state, over 6 percent of residents, three times the national rate, are now believed to have a “gambling disorder.” The Center says the percentage of state residents with a less severe “gambling problem” is about 15 percent, also nearly triple the national rate.

Center director Nower says the fastest growing cohort of sports bettors in the state are aged between 21 and 24. She says only about one percent of those young bettors make use of “responsible gambling” measures like play limits or self-exclusion that sportsbooks and casinos are legally required to offer them.

States Ride the Wave

Now 36 states have legalized sports betting—it’s operational in 33 states, with three more set to launch—and 26 have also legalized mobile sports betting. Eight more states have pending legislation or voter referendums in the works.

It’s big business. According to the AGA, in 2022 Americans bet a record $93.2 billion legally on sports, the second record year in a row. All those bets generated $7.5 billion in revenue for sportsbooks, a 73 percent increase over 2021.

Regulations on sports betting vary by state. All come with age limits (for most it is 21) and the requirement that you be physically in the state when you bet. Most require ads to include contact information for gambling helplines. Many allow bettors to exclude themselves. Some prohibit some or all betting on college games. Some permit bets only on the outcome of games and prohibit prop bets.

Curiously, it’s not only states that have legalized sports betting that are seeing related spikes in problem gambling. Newsweek’s analysis of state gambling hotlines, for instance, found that calls to the gambling helpline in California, where sports betting isn’t allowed, shot up more than 70 percent last year. In Florida, where most sports gambling isn’t operational, the Florida Council on Compulsive Gambling reports that outreach to its helpline was up 140 percent in fiscal 2021-2022, compared to fiscal 2018-2019. Gamblers have been able to avoid the in-state ban either by using virtual private networks which hide their location or by making bets with illegal offshore sportsbooks.

As in states where online sports betting is legal, the Florida Council found that most callers who said they gamble online were male (86 percent) and the most common type of gambling for them was on sports (55 percent). It also similarly found that callers were getting younger, noting a 56 percent increase in gamblers 25 or under. Most worrisome, “This year’s data reveals higher levels of anxiety (62 percent), depression (63 percent), and neurological disorders (20 percent) reported compared with HelpLine data from last year. Of significant note is that almost one-quarter (24 percent) disclosed suicidal ideations or attempts by the gambler, reflecting a 50 percent increase from the previous fiscal year.”

John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe/Getty

One outlier in all of this is Oregon. Although sports betting has been legal since late 2019, the state hasn’t had an increase in helpline calls. It is not clear why. Oregon doesn’t have any major professional teams of its own. There is only one large gambling vendor, the state lottery, which controls most sports betting in the state and one legal mobile sports betting operator, DraftKings. As a result, according to Oregon Health Authority spokesperson Tim Heider, Oregon has been spared some of the sports gambling ad onslaught. “Other states have been bombarded with sports betting advertisements, multiple competing vendors and a developing regulatory environment,” he says.

‘It Will Be a Huge Problem in the United States’

Gambling addiction experts view sports bet- ting in the U.S. as a time bomb. Rutgers’ Nower says, “It’s unlikely we will see the full effect of this rush to legalization for several years.” Part of the reason is that addiction to gambling is quieter than addiction to drugs or alcohol. “Gambling addiction has no tell,” Nower says. “You can be gambling away your house on your mobile phone sitting at the dinner table, and not a single person will know until the devastation of your whole family is complete.”

The experiences of other countries with legal gambling offer clues to where the U.S. may be headed. In the U.K., which has a long tradition of legal gambling, mobile betting became legal in 2005. In 2016, Stewart Kenny, co-founder of the online sports betting site Paddy Power, stepped down, saying he was ashamed for having popularized online betting and felt some responsibility for an uptick in addiction and suicides. According to a U.K. government report, more than 400 suicides a year are linked to gambling. In 2019 the government opened its first gambling clinic for children, citing findings that 55,000 of the country’s estimated 395,000 problem gamblers were kids aged 11 to 16. Kenny recently warned on Bloomberg‘s The Big Take podcast, “It will be a huge problem in the United States…a society that accepts some people fall through the cracks.”

Australia, which had taken a freewheeling approach to gambling, has in recent years instituted some restrictions, including limits on TV advertising and requiring gamblers to set an annual deposit limit for themselves. Sally Gainsbury, director of the University of Sydney’s Gambling Treatment and Research Clinic, says, “America has an opportunity now to do what we’re trying to do retrospectively, which is to encourage low-risk gambling.”

Gainsbury says it is typically nine to 10 years after someone develops a gambling problem that they seek treatment. “Left unchecked, I expect there will be a substantial rise in gambling problems related to online wagering, which is going to have a massive community detrimental impact, and not only for these individuals and their families, but the whole community.”

The likelihood of any significant new restrictions on gambling in the U.S. any time soon, however, seem dim. The federal government, which could regulate interstate aspects of legal state gambling, has so far stayed on the sidelines. According to Rutgers’ Nower, “The federal government has been completely silent.” She adds, “The federal government needs to step up to the plate. They get an enormous amount of tax revenue from gambling winnings. There needs to be an office of problem gambling.”

Several states are considering measures to ban or limit gambling advertising. John Holden, an associate professor of management at Oklahoma State University who studies sports gambling regulation, however, recently told CNN, “A lot of state regulators have big First Amendment fears. No one wants to fund litigation or lose a Supreme Court case over gambling.” This February U.S. Representative Paul Tonko, a New York Democrat, introduced the “Betting Our Future Act,” which would ban all sportsbook advertising on the internet, TV and radio but no significant action has been taken on the bill.

Jacquelyn Martin/AFP/Getty

Meanwhile, in 2021, nine states didn’t report any dedicated funding at all for problem gambling, according to the Survey of Publicly Funded Problem Gambling Services. Of the 42 states with specifically funded problem gambling services, average annual per capita spending on the programs was only about 40 cents. For perspective: In the U.S., substance use disorders are about seven times more common than gambling disorders, but public funding for substance abuse treatment is about 338 times greater than public funding for all problem gambling services.

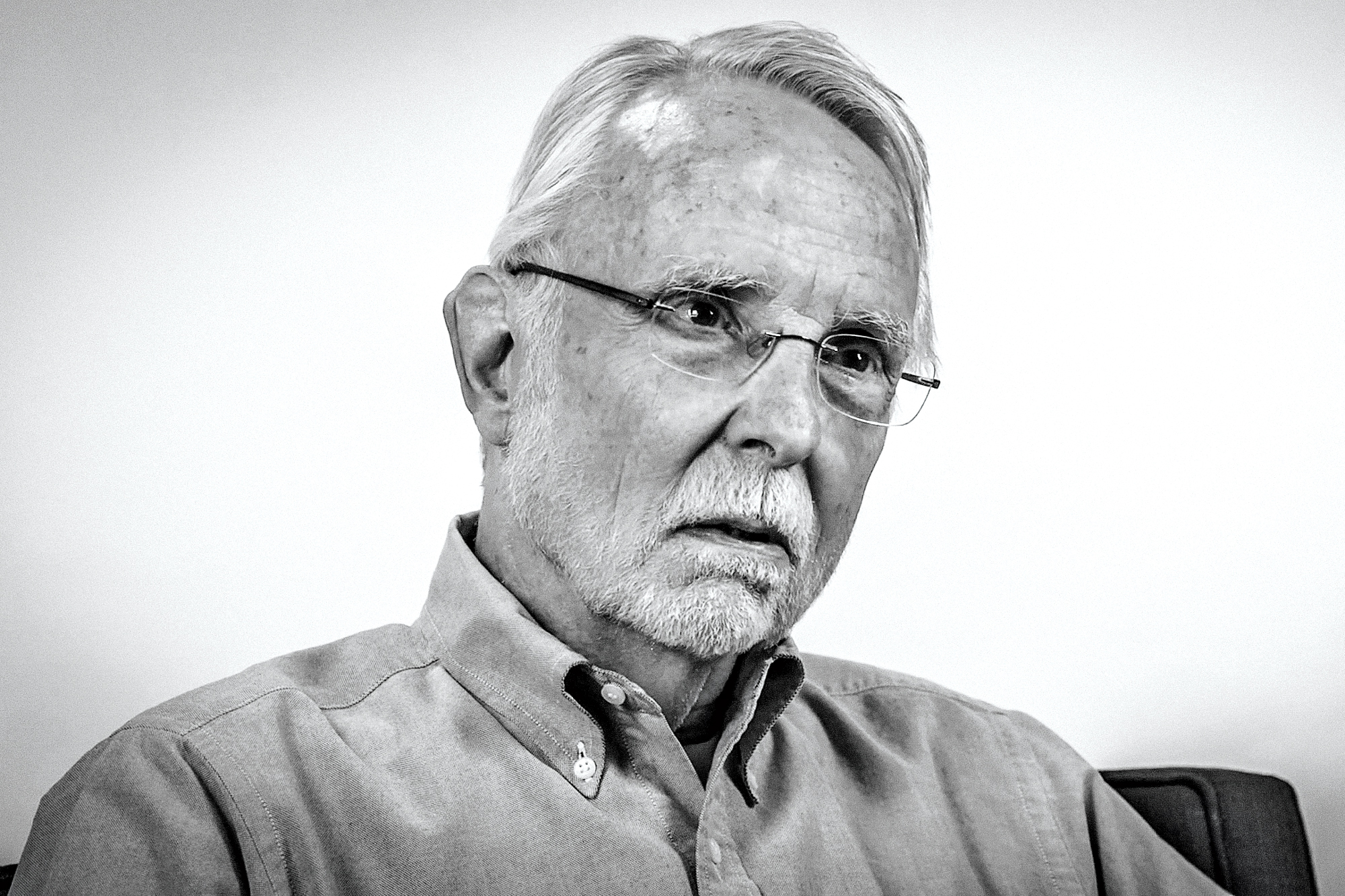

Courtesy of Nebraska Commission on Problem Gambling

David Geier, director of the Nebraska Problem Gambling Assistance Program, says the biggest obstacle to an effective response to the increase in problem gambling is the patchwork of state laws regulating gambling and funding help for those who get into trouble

“There are programs like ours in 42 states.” he says. “Some of them have some government funding, some have none. Some rely on volunteers. We’re lucky in Nebraska, we have some funding that comes to us because of a variety of laws that had set it up. But it’s inconsistent and uneven nationwide, right now.”

Better funded programs in other countries, like the U.K, Australia and Canada, point to a positive way forward but Geier, for one, isn’t optimistic they will be adopted here, now or in the future. “The U.S. just hasn’t caught up,” he says. “And it doesn’t appear likely that it’s going to happen in our lifetimes.”