NORTH SIOUX CITY — In the long-ago days when gambling was confined to racetracks, Sodrac reigned supreme.

The Sodrac Park greyhound track in North Sioux City, just off the southbound lanes of Interstate 29, opened in 1955. Sources differ on the meaning of the Sodrac name — it was an abbreviation either for the Southern Dakota Racing Club or the South Dakota Racing Commission; archival materials exist to support both possibilities.

In the 1950s, Sodrac was one of three racetracks just outside Sioux City — and outside Iowa state lines — along with the Tri-State horse track two miles north of Sodrac, and the Atokad horse track in South Sioux City. Gambling was illegal in Iowa at the time, but South Dakota and Nebraska allowed gambling at racetracks.

Atokad is the only one that remains, though races are held there only once a year; its enormous grandstands have been replaced with modest bleacher seats.

People are also reading…

Greyhound races at Sodrac Park were hugely popular in the 1960s and 1970s. The racetrack declined in the 1980s and closed down in the 1990s.

Greyhound racing (and to a greater extent, horse racing) was hugely popular in the middle of the last century, in part because it was the only legally sanctioned form of gambling in states that allowed it. Smaller greyhound and horse racetracks entered a terminal decline around the time that states began loosening their gambling laws, permitting casinos and lotteries.

When the 60-day greyhound racing season closed at the end of Sodrac’s first summer, the parimutuel handle (the sum of all wagers) came out to more than $3.1 million, described as an “astounding figure” in contemporary news coverage. On the final night of that season, Sept. 15, 1955, a record $120,520 passed through the betting windows, surpassing the record set the night before of $101,000.

The annual handle peaked at around $26 million in 1984; a rapid reversal of fortune set in not long after that high water-mark. The track reportedly welcomed as many as 25 to 28 busloads of gamblers a night in its better days.

“There would be huge buses, huge crowds bused from Kansas City, and bused from Minneapolis, and the parking lot would just be packed,” said Jeff Donaldson, 58, who was employed as the track’s announcer in the 1980s.

Donaldson’s present-day home in North Sioux City was built on the former Sodrac property.

The annual betting handle at North Sioux City’s Sodrac Park peaked in 1984 at roughly $26 million, not adjusted for inflation.

Colorful owners

Beginning in 1960, Sodrac was owned by colorful, out-of-state gentlemen — that year it was purchased by Jerry Collins, a high school dropout, self-made-millionaire Floridian and state politician; during his lifetime, Collins owned greyhound tracks in Florida, Colorado, Oregon and Cuba, along with four circuses.

Sodrac was briefly the subject of a race-fixing scandal in the first year of Collins’ ownership: On July 29, 1960, a group of three Miami men reaped huge profits by betting on an implausible combination of long-shot dogs. Somehow or other they’d arranged to give barbiturates to the dogs favored to win the races. Three trainers and dog-owners were subsequently fined $50.

“We feel we have uncovered a national betting ring,” Collins said at the time.

Years after he parted ways with Sodrac, in 1987, Collins made headlines nationwide when he wrote a $1.3 million personal check to the televangelist Oral Roberts. In March of that year, Roberts announced that God had ordered him to end his life with a hunger strike unless he could raise millions of dollars for Oral Roberts University. Collins, who was still active in the dog racing industry, answered that call.

Collins sold the track in 1974 to Joseph M. Linsey, a septuagenarian ex-bootlegger of the Prohibition era who later made millions in legal liquor distribution and dog tracks in several states. The publicity-averse Linsey lived on the East Coast and wasn’t much of a presence at Sodrac; the track’s day-to-day operations were largely handled by Irving Epstein, the track’s manager.

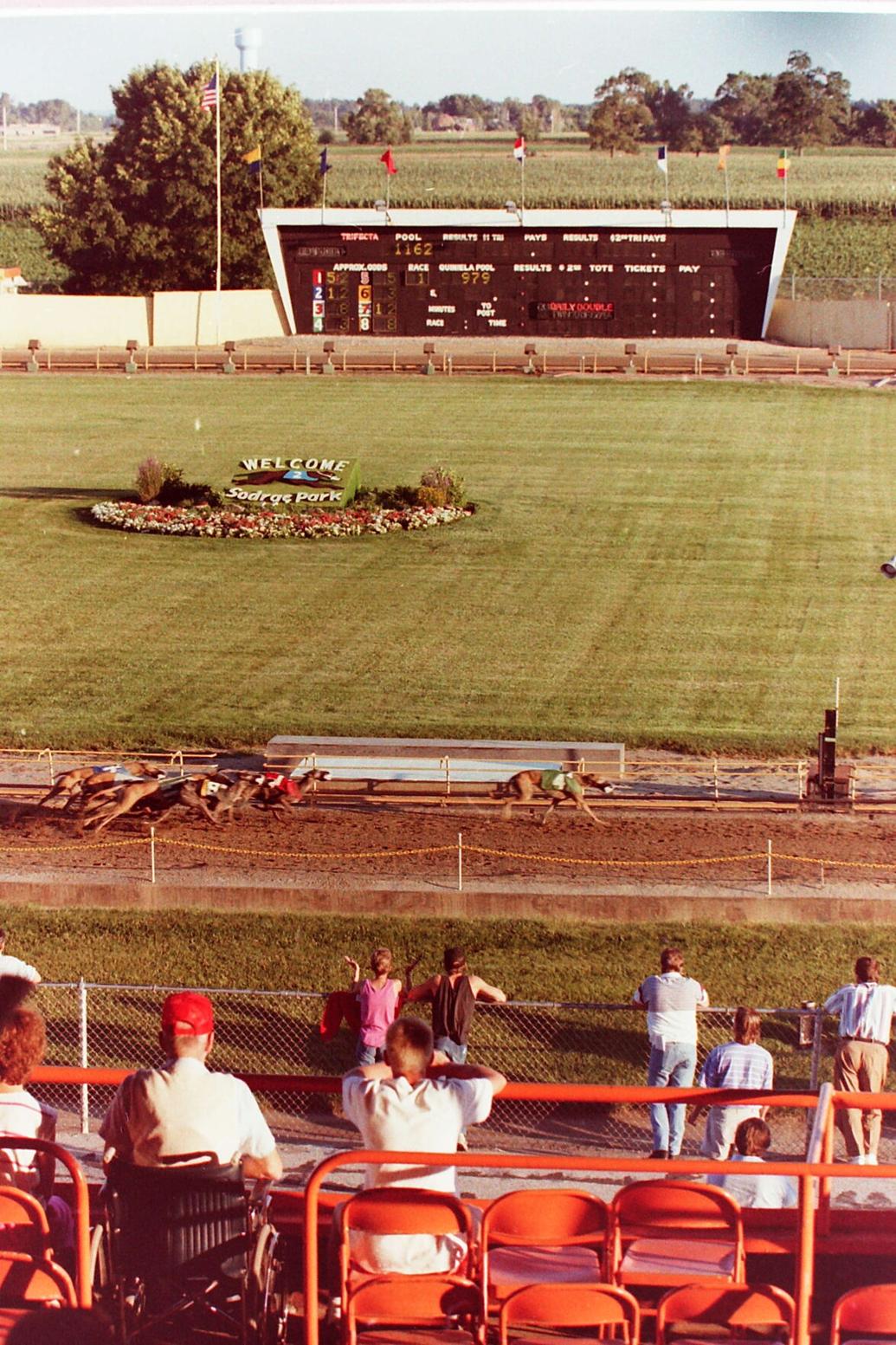

Sodrac Park, shown here in 1991, saw roughly 300,000 visitors during its best years. The track declined rapidly after states began loosening t…

A steady drumbeat of news reports indicating that Linsey had connections to organized crime were vehemently denied in 1974 by Alfred S. Ross, Linsey’s nephew and business associate who later co-owned Sodrac.

Then-South Dakota Gov. Richard F. Kneip said the state investigated the sale of the track and was satisfied that nothing was amiss with Linsey’s background. Linsey had in fact spent a year in prison in 1927 for his bootlegging activities and had come to the attention of state and federal agencies, including the FBI, on a number of occasions. He also had documented acquaintanceships with several Mafia people, which he acknowledged — still, he denied any direct ties.

Linsey, who lived to be 95, unloaded the track before the 1990 racing season. By then Sodrac was on death’s doorstep.

Vince Wuebker worked at the track as a young man during its latter years, in the late 1980s and early 1990s; his job title for the first two years was public relations (“I don’t know what my job was,” he said, but it involved some writing and also running bets). He later became the track’s announcer after Donaldson left.

“I always called it the Fenway of dog tracks, because it was so old,” said Wuebker, now 57 and a resident of Fargo, North Dakota.

“Sodrac was just, in a good way, it was a dump,” he added.

Sodrac Park, shown here in 1991, was not the first dog track to operate in North Sioux City; an earlier dog track ran races near the airfield during the mid-1930s, and reportedly was visited by the legendary bank robber Baby Face Nelson.

Not the first greyhound track

Sodrac was not the first dog track to operate in North Sioux City — another had operated near the airfield there during the mid-1930s. (North Sioux City at that time was called Stevens, South Dakota.) That dog track, operated by a firm called the Dakota Racing Stables and Amusements Company, opened in the summer of 1934.

On its busier days the track reportedly attracted more than 3,000 people with as many as eight races a day, according to contemporary Journal coverage.

A month after that track opened, in August 1934, the Associated Press reported that the legendary bank robber Baby Face Nelson — who was gunned down three months later — was spotted at the dog track. (The veracity of his alleged visit to the track is unclear, though the Sioux City Police investigated, and Union County Sheriff Tom Collins, who “made a nightly check of of the crowds at the dog races,” told The Journal he hadn’t seen Nelson there.)

The Sodrac Park greyhound track, shown here probably in the 1960s, once attracted busloads of gamblers from Omaha and other distant points.

‘Probably the area’s largest industry’

In its time Sodrac was a moneymaker, and respectable enough that at the end of the 1971 racing season, Gov. Kneip was a featured guest, in honor of the track’s longtime charitable contributions.

The majority of Sodrac gamblers came from other states. In 1981, Jim Masmar, then the Siouxland Chamber of Commerce administrative vice president, called Sodrac “undoubtedly one of the biggest boosts to Sioux City’s economy.” Epstein, the track manager, said it was “the leading tourist attraction in Siouxland.”

During its best years Sodrac would see roughly 300,000 people cross its threshold annually. The track was conservatively estimated to stimulate the Siouxland economy to the tune of $5 million a year, while the State of South Dakota took in $2 million a year in taxes from the racetrack.

Sioux City had suffered economic reversals during the 1970s: “The past few years have not been thrilling,” Epstein said in 1981. “Sioux City is so economically depressed it’s a wonder people are even willing to leave their homes.”

But Sodrac didn’t suffer at all.

“We’re probably the area’s largest industry,” Epstein said at the time. “The money we generate is staggering.”

“Sodrac was just, in a good way, it was a dump,” said Vince Wuebker, who worked at the North Sioux City greyhound track in the late 1980s and …

Decline came swiftly

Flash forward to the late 1980s, and Sodrac was dying by a thousand cuts. A competing dog track in Council Bluffs, called Bluffs Run, siphoned the bettors from the Omaha and Kansas City metros. Iowa legalized the lottery in 1985, followed by South Dakota.

Other states were legalizing dog racing. Soon casinos opened in Sloan and Onawa, Iowa, and North Sioux City welcomed video lottery machines. And a riverboat was on its way to Sioux City.

“On the weekends, you would get a decent crowd,” Wuebker said of the late 1980s and early 1990s. “But during the week — you were always reminded by the old-timers how busy it used to be, like in the ’60s and ’70s, when they’d bring busloads up from Omaha every night and it was packed.”

North Sioux City firefighters battle a blaze at the old Sodrac Park racetrack Friday, April 24, 1998. The buildings at the park were in the pr…

1985 was the last year Sodrac still held a vestige of its quasi-monopoly on greyhound bets in the region; that year, $22.8 million was wagered by 248,793 visitors. A year later, in 1986, only $10.5 million was bet at Sodrac, and the number of visitors had been cut to 125,429. In an effort to woo back visitors, Sodrac underwent a refurbishment in 1987, and by 1991, the track installed video lottery machines to compete with the other video lottery terminals in North Sioux City.

It wasn’t enough. In 1993, the year the Sioux City Sue riverboat casino came to Sioux City’s riverbank, the track announced it wouldn’t offer live dog racing, which had become unprofitable; the state’s other dog track in Rapid City ended its races the year prior, and live dog racing was finished in South Dakota.

For a time Sodrac offered simulcasts of other races, which remained a profitable venture. The track’s bleacher seats, kennels, bar, decoy rabbit, urinals and all other physical assets that could be moved went on the auction block in October 1996. The final humiliation came a year and a half later, on April 24, 1998, when Sodrac’s Kennel Club building — then in the process of being demolished to make way for new development — burned down.

After the end of this 2022 season in May, the Iowa Greyhound Park track in Dubuque, Iowa, will close for good. By the end of the year there will only be two tracks left in the country. It’s been a long slide for greyhound racing, which reached its peak in the 1980s when there were more than 50 tracks scattered across 19 states. Since then, increased concerns about how the dogs are treated along with an explosion of gambling options has nearly killed the sport.