HONG KONG, Sept 29 (Reuters Breakingviews) – Chinese gamblers are heading back to Macau after almost three years, but the odds on a full recovery in what was the world’s largest gambling hub are long.

Authorities’ decision to allow tour groups to visit the Chinese enclave from November onwards is raising hopes that crowds will once more throng the betting rooms and boulevards of the Cotai Strip in the former Portuguese colony and flock to gaudy landmarks like the miniature Eiffel Tower.

Visitors from across the border in China, where gambling is banned, are Macau’s lifeblood. They accounted for 71% of arrivals before the pandemic, with another 19% coming from Hong Kong, according to the tourism board. In their absence, Macau’s economy in the first half of 2022 was nearly two-thirds smaller than in the same period in 2019.

Casinos have supported heady growth since 2002 when Macau opened the market to multiple operators. Before Covid-19 struck, gambling accounted for 80% of the government’s revenue, half of its GDP, and more than a fifth of jobs, per official data. Macau’s tiny population of 680,000 was nearly 70% richer on a per capita basis than their peers in Hong Kong, per the International Monetary Fund.

The travel news understandably inspired a mini-relief rally: Hong Kong-listed stocks for Macau casino operators Sands China (1928.HK), Wynn Macau (1128.HK), MGM China (2282.HK), Melco Resorts , SJM Holdings (0880.HK) and Galaxy Entertainment (0027.HK), with a combined depressed market capitalisation of $56 billion, jumped around 10% on Monday.

They look confident. The six existing operators also submitted applications this month to re-bid for long-term licences. There’s a new competitor too, Malaysia’s Genting group. But their collective enthusiasm masks an awkward reality: Macau’s dependence on the gambling industry looks increasingly fraught.

GAMBLING ON GAMBLING

Optimists point out that Las Vegas has enjoyed a robust recovery. After relaxing pandemic controls last year, Nevada logged a monthly gaming revenue of $1 billion or more for 17 consecutive months through to July, a record, according to C3 Gaming consultancy.

Macau will need longer to spring back. Some 13% of Macau’s non-resident workers had departed by the end of 2021, per official data. Analysts reckon revenue at the six Macau-focused casino operators will recover to 80% of 2019 levels by 2024. If revenue continues to grow at 30% per annum as they expect, it will take another year for a full rebound.

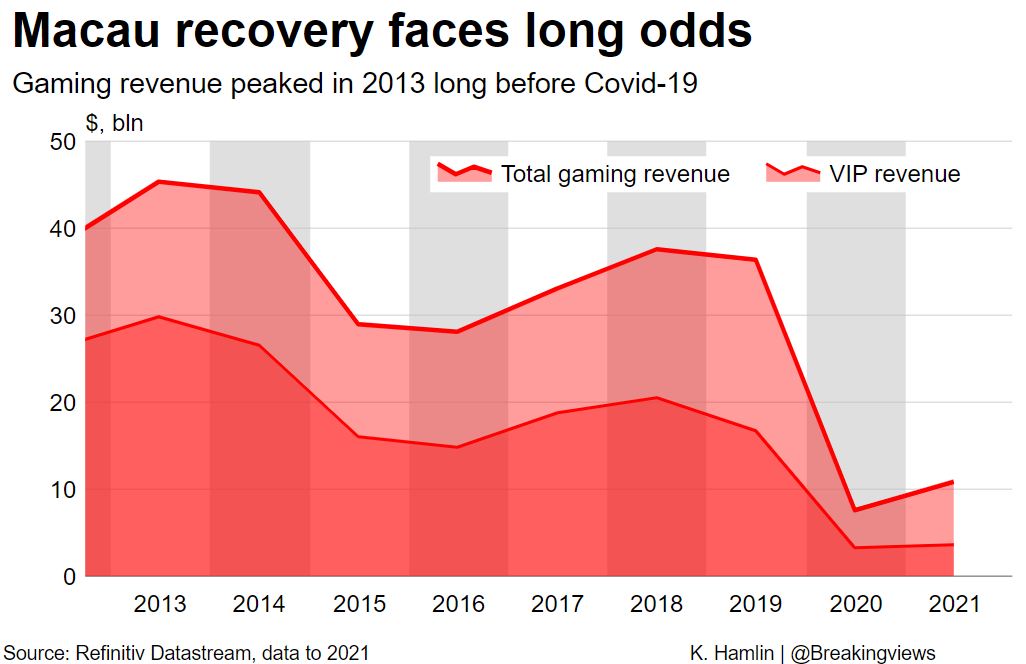

That trajectory assumes no further crackdowns on an industry already deeply impacted by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s 10 years in office. His earlier anti-graft campaign scared away the biggest spenders. Gaming revenue, which peaked at $45 billion in 2013, has never recovered from the blow to VIP business, sinking to $36 billion by 2019, per Macau’s Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau.

This year there have been fresh restrictions imposed on so-called junkets, organisations arranging travel and credit. An ongoing court case against Alvin Chau, the former boss of Suncity, which previously bankrolled around half of Macau’s VIP play read more , shows the industry is still on Beijing’s radar. Waving goodbye to the high rollers matters less for the casinos in the medium term because EBITDA margins in the mass market are almost double those for high rollers. The risk is the mass market becomes a target too.

Macau now depends on China’s rising middle class frittering away their hard-won savings at slot machines and baccarat tables, including those owned by foreign firms such as Sands, Wynn and MGM. Xi’s recent policies, including his “common prosperity” drive, suggest there is little tolerance for unnecessary spending. Other industries that failed to fit with these vaguely defined directives have faced dramatic consequences. New rules shuttered China’s once booming private tuition sector and crushed video game giant Tencent (0700.HK).

Sensing the vulnerability, officials have been eager to diversify Macau for many years but efforts so far have been half-hearted. Ironically, the government depends on the casinos themselves to drive change by pushing them to offer more wholesome entertainment like dance shows and water parks. Other schemes, such as plans to foster the financial industry, are at an early stage. Some ideas, including a mooted sovereign wealth fund in 2019, never got off the ground at all.

The casinos serve a purpose. The industry underpins the economy of one of China’s special autonomous regions, as finance does for Hong Kong, and more than a third of revenue is claimed as tax. Eradicating all legitimate options could force China’s would-be punters to seek out illegal alternatives. Nonetheless, Macau increasingly looks like a house of cards.

Follow @KatrinaHamlin on Twitter

Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.com

Editing by Una Galani and Thomas Shum

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

Opinions expressed are those of the author. They do not reflect the views of Reuters News, which, under the Trust Principles, is committed to integrity, independence, and freedom from bias.