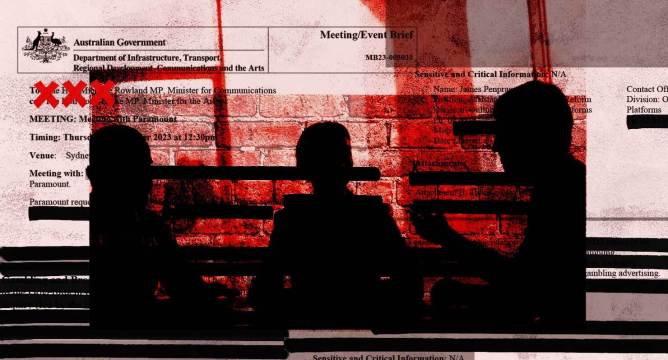

This article is an instalment in a new series, Punted, on the government’s failure to reform gambling advertising.

A journalist soon reconciles themselves to the idea that most of what they say is weightless, pointless and instantly perishable. But just occasionally, something hits the mark — as when, six weeks ago on the ABC’s Offsiders, I was asked to respond briefly to the appointment of Gillon McLachlan as CEO of Tabcorp.

I can’t say that McLachlan over the years has left much of a mark on me, albeit that he seems to have been hugely overpaid and overpraised for the herculean task of selling football to Australians. Oh, and he talks like a corporate robot — a standard he maintained when commenting about his new job: “It’s a legacy Australian brand in the entertainment space. I resonate with both of those things.”

I proceeded to liken the relationship between sport and gambling to that which used to exist between sport and tobacco — the use of something wholesome to mask the taste of something toxic, with the intention of addicting the user.

I then got up, walked out, and didn’t think of it again, because, well, it’s obvious, isn’t it? All those mirthless advertisements in which interchangeable Aussie bogans clown around as though gambling is just a jolly caper in which nobody ever loses are part of a relentless campaign of “funification”. The deadset giveaways are the token warnings that follow, modelled on those that once trailed cigarette advertisements.

Anyway, it seems sometimes the obvious needs saying: thanks to the infinite loop of social media, I continue finding the remarks to be a conversation starter. “I like that thing you said,” somebody will comment before commencing their own monologue, ranging from the antisocial impacts of addictive betting apps on family, friends and themselves to how gambling advertisements are rendering televised sport almost unwatchable, especially in the presence of children.

Which is interesting, even if I’m not sure I completely nailed what was, in the end, a throwaway line, omitting as I did the complicity of government, happy to rake off taxes, levies and donations while dithering over the 31 recommendations of “You Win Some, You Lose More” — the far-reaching report by the House of Representatives standing committee on social policy and legal affairs, submitted more than a year ago, on the pernicious infiltration of online gambling into everyday life.

Still, at least I remembered to reference the “lush, matey world” McLachlan inhabits, with its common cast of personalities and its heady swirl of betting, sport, entertainment, media, masculinity and crony capitalism. For it’s that disarming blurring of interests that is busily debauching something we love, our games and recreations, by mixing them with something about which we would otherwise be properly wary, the gambling industrial complex.

Sometimes this is overt, as when the National Rugby League launches its season in Las Vegas. But most of the time, modern gambling presents like it is hardly gambling at all — it positions, rather, as an adjunct to watching and enjoying, seeding the notion that maybe a little punt will enliven the experience, deepen our involvement, express our affinity.

This is not gambling on sport; this is gambling in sport, aiming to be indivisible from it. Why, it is almost as though we are participating by proxy. What better way to show how much we care, how invested we are? We hear that admonition to “gamble responsibility” but know it’s not for us. We’re grown-ups, aren’t we? We know sport, don’t we? What red-blooded Aussie bloke does not? Besides, it’s an Australian birthright, eh? Dad would have bet on two flies on a wall. How much would he have enjoyed a same-game multi offering a range of flies on a host of walls?

Gambling, moreover, is always cosying up to us, its apps snug on our phones among apps that helpfully navigate our driving routes and advise us of the weather. Imagine if cigarette packets had been self-replenishing; imagine if cigarettes lit themselves. Because the exertion required to bet is now so minimal, it can be done almost unconsciously, as one might drag on a vape. We forget that this is not for our convenience; it is for the convenience of the faceless powers who rolled these apps out.

Now, you can cavil about the resemblances between tobacco and gambling — such propositions are inherently inexact. You can complain, for example, that while there is no healthy level of smoking, it is, by healthy restraints and close study, possible to bet expertly and in relative safety. But this recalls those hoary anecdotal defences of tobacco, that you had a grandma who smoked 50 a day and lived to 95. No, not everyone is affected the same way. But Australians, just as they were tremendous smokers, have become tremendous losers — $25 billion a year according to one, albeit dated, figure. Nor can you sidestep the common influence of the gravest addiction of all, that of sport to money.

There’s no mystery about the financial imperatives on sport’s side. Betting companies first began courting sports at around the time of the global financial crisis, as banks and financial institutions, traditional sources of sponsorship revenue, began to withdraw their favours. Their influence has grown as the value of broadcast rights has plateaued.

Sport is always in need of a buck; sport is always finding new needs, new wants; sport is always spending more than it has, then complaining of what it cannot afford. What more benign partner than a growing industry with seemingly parallel enthusiasms? If we just hold our noses a little, we can all get rich, can’t we? After all, if it’s good enough for the GillBot…

Anyone affected by problem gambling can get immediate assistance by calling the National Gambling Helpline on 1800 858 858 for free, professional and confidential support 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Will sport ever be able to free itself from the noxious grasp of the gambling industry? Let us know your thoughts by writing to [email protected]. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.