Addiction to gambling and other harmful products such as vaping is affecting children’s ability to learn and concentrate at school during a critical time in their brain development, the CEO of the Association of Heads of Independent Schools of Australia, Dr Chris Duncan, has warned.

“I’m teaching many kids with chronic mental health issues related … [to] these areas,” he said.

“The state of mind of kids is being altered because of these harmful industries.

“And when kids are in a certain sort of mental state, they’re not conditioned to learn anything at school, they’re not able to focus,” he said.

This week a Guardian Australia investigation revealed a 16% increase in the number of young people seeking help for gambling, with youth entering adulthood with debt and depression. It’s a trend that education professionals say they are seeing evidence of in classrooms.

Duncan said it can be frustrating to see media reports about Naplan results “and wringing our hands about schools not doing enough, and the teachers not being good enough”.

“But these are the issues teachers are dealing with,” he said. “Organisations are using technology to get kids addicted to stuff.

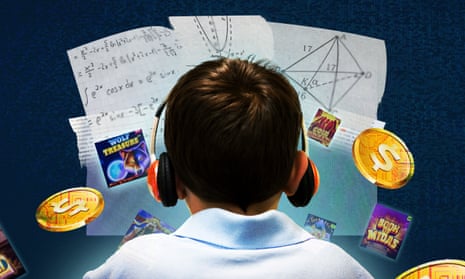

“Many video games … verge on gambling in terms of the noises and the kind of rewards in the game. And we would argue it’s a process of normalisation or conditioning at work.”

Teresa* told Guardian Australia she was working at a “decent” high school last year and witnessed the “massive gambling problem in the soon-to-be grads”.

“The ones over 18 all had sports bets app accounts and largely encouraged younger teens to sign up,” she said. “They gambled before, after and in class, they often took money from younger peers to make bets for them. The teachers did their best to educate and discourage, but it was prolific.”

A former student, Alex*, told Guardian Australia that at his private boys high school in Melbourne “there was consistently a group of 15 to 20 boys on Sportsbet either skipping classes or [using it] during lunch”.

“They would get their parents or older siblings to sign them up and then proceed to use their allowance money on it,” he said. “It was spreading in popularity with even younger boys by the time I graduated.”

The chief executive of Independent Schools Victoria, Michelle Green, said gambling among school students both in public and private schools was “exacerbated by relentless saturation advertising” by gambling companies.

“The growing incidence of gambling by young people, including school students, is an issue of serious concern to all schools and parents, regardless of sector,” she said.

“Principals and teachers know this is a growing problem.

“It’s clear from the proliferation of gambling in society that this is not an issue schools can tackle on their own – it’s a community-wide problem which requires a coordinated response, including from governments.”

A study on sponsorship of sport by various industries including food, alcohol and gambling, published in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, found: “There is strong evidence to suggest that children, especially those under eight years old, are extremely susceptible to marketing because they do not have the experience or cognitive skills to critically evaluate the messages being promoted.”

A professor of public health with the Australian National University, Emily Banks, said: “Addiction pathways are set down in adolescence.

“You are setting up patterns by gambling in adolescence that set up feedback loops for addiction,” she said. “It’s why these industries actively try to get people addicted as teenagers, because then they have lifetime customers. The scale of the problem is huge.”

In a school-wide bulletin issued to the Carey Baptist Grammar School community in Kew, Victoria, the deputy head of senior school, Christian Gregory, wrote he was “quite startled with the sophistication of gambling the students know and conduct regularly”.

Gregory wrote that a student asked him who he thought was going to kick the first goal in an upcoming footy match, and he responded ‘Kosi Pickett’.

“The following Monday when I bumped into this particular student, he thanked me for this info and said it was a cracking multi,” Gregory wrote.

A multi bet combines a series of bets into one wager.

“Gambling among school students is on the rise,” Gregory wrote, adding that the school was among several in Victoria trying to raise awareness of gambling among youth.

after newsletter promotion

Prof Alex Russell, a principal research fellow with CQUniversity’s experimental gambling research laboratory, said young people were bypassing the requirement to be over the age of 18 to access gambling products.

While there were age checks at the door at physical establishments, Russell said school age youth were either using fake IDs or finding smaller venues that don’t check as often or as rigorously.

Meanwhile, online platforms make it even easier to get around the age requirements as they don’t check age each time a bet is placed, Russell said. “With online, once you’ve got an account you’re pretty much good to go. If you can get through that initial check, then you’re able to gamble.”Russell said there were also “real grey areas” when it comes to the digital environment. For example, loot boxes in video games were “pretty much a gambling product”, Russell said, but they were still not treated as such.

Q&A

How do kids gamble with ‘skins’ and ‘loot boxes’?

Show

Many young people are first conditioned to gamble through video game features such as “loot boxes” and “skins”.

Loot boxes are virtual items – which can either be purchased or earned in video games – that contain randomised rewards, some of which are more rare and valuable than others. Experts say loot boxes are “psychologically akin” to gambling because they share many characteristics – like the exchange of money for an unknown outcome, determined by chance.

Skins are virtual items that can either be earned as a reward through in-game play or be bought from within the game, often through loot boxes. Skins are usually cosmetic; they could change the appearance of an in-game weapon, or the look of a character, for instance, but most have no impact on play. Some skins are considered so prestigious and uncommon that they have become a form of virtual currency and can be resold on secondary markets for thousands of real-world dollars. Skins can also be used by gamers to place bets on the outcome of online gaming and sports on third-party sites.

Kids can earn skins or loot boxes through play in video games, or they can buy or be given gift cards for various online marketplaces such as Steam, and use those cards to buy the skins or loot boxes.

They then visit third-party casino sites (which are not affiliated with the game directly) and use the skins or loot boxes as a form of currency to gamble – either wagering them directly, or depositing them with the site in exchange for the site’s own currency.

The types of casino games played can vary from simple roulette to betting on video game match results. Players can cash out their winnings by converting them into different virtual skins (which can often be resold for real money), cryptocurrencies, or simply for cash.

As the casino games are not technically being played “for money”, they do not fall under gambling regulations. Belgium and the Netherlands are among the countries that regulate loot boxes as a form of gambling, but they are currently not regulated in Australia.