© Kareem Elgazzar/The Enquirer Installation of a new playing surface continues at the University of Cincinnati Baseball Stadium, Monday, June 12, 2023, in Cincinnati. The university is set to move into the Big 12 Conference in July.

Before Bert Neff stepped to the window to place his wager on April 28, the staff at the BetMGM sportsbook at Great American Ball Park suspected something about him wasn’t right.

He said odd things about his bet that worried some of the employees. He was keenly interested in an Alabama-Louisiana State college baseball game almost 900 miles away. And he wanted to put down so much money on the game that the sportsbook rejected his first wager.

When sportsbooks elsewhere began noticing questionable bets on the same game a short time later, investigators say, suspicion turned to action: They alerted authorities and suspended betting.

Start the day smarter. Get all the news you need in your inbox each morning.

“In some cases, the evidence is more clear than others,” said Matt Holt, CEO of U.S. Integrity, the private monitoring firm that conducted the initial investigation into the April 28 bet in Cincinnati.

“In this case,” he said, “it was pretty clear, pretty quickly.”

Holt and others involved in the investigation wouldn’t discuss all the evidence they turned up that day, but the decision by sportsbook employees to question Neff’s wager set in motion a series of events that shook college sports and upended baseball programs at the University of Alabama and the University of Cincinnati.

Three people, including Alabama head coach Brad Bohannon, lost their jobs after the April 28 bet because of their connection to Neff, the father of a UC baseball player. Weeks later, UC head coach Scott Googins resigned.

The turmoil at both programs is a stark reminder that the expansion of sports betting to more than 30 states since the U.S. Supreme Court legalized it five years ago is a high-stakes risk not only for gamblers, but for those who play and coach the games.

Even with high-tech monitoring and a well-trained sportsbook staff to catch suspicious wagers like Neff’s, the sheer volume of bets placed every day by the nation’s 39 million sports gamblers is a growing challenge.

Regulators, leagues, athletes, coaches and administrators all are learning on the fly how to navigate a world in which sports wagers that were illegal just a few years ago are now placed thousands of times a day on phones or in person.

Cheating is a threat. And as sports betting has grown, so has the campaign to stop bettors from directly influencing games or using inside information to gain an advantage.

“How much are they catching? Honestly, probably not a lot,” said John Holden, an Oklahoma State University business professor who has written dozens of papers on sports and sports gambling.

He said the incident in Cincinnati, along with other recent gambling scandals in pro and college sports, suggests more trouble may be on the way.

“If that is the entire iceberg, as opposed to the tip of the iceberg, I’d be absolutely shocked,” Holden said.

‘Red flags’ went up before bet was placed

Those connected to the monitoring and regulation of sports betting see it differently. To them, the system did what it was supposed to do April 28, from the moment Neff walked into BetMGM seeking to place a bet on the Alabama-LSU game to the moment regulators halted betting on the game.

Almost immediately, the sportsbook staff identified the bet as a potential problem, said Jessica Franks, spokeswoman for the Ohio Casino Control Commission, which regulates sports betting in Ohio and is investigating the matter.

© Erin Couch/Cincinnati Enquirer BetMGM on Sunday debuted a 6,244-square-foot space featuring 15 betting kiosks and three betting windows at Great American Ball Park.

She said the sportsbook staff then notified the commission and U.S. Integrity, which alerted sportsbooks across the country to the possibility that betting on the Alabama-LSU game had been compromised.

“There were a number of things that raised some red flags,” Franks said.

Though she wouldn’t say what, exactly, caused those red flags to go up that day, Franks said surveillance video as well as the observations of sportsbook employees would be relevant to the investigation.

“The staff are trained in what to look for,” she said. “For people who’ve worked in gaming a long time, they know when something doesn’t look quite right.”

In this case, Holt said, several things didn’t look right, including the bettor’s comments and the attempt to place a large wager.

Holt wouldn’t describe the comments or the wager in more detail, deferring to state investigators, but he said the sportsbook later accepted a bet for a lesser amount. Officials at BetMGM did not respond to emails seeking comment.

Neither Franks nor Holt would confirm Neff was the bettor on April 28, but multiple sources have told The Enquirer he placed the bet. Neff, of Mooresville, Indiana, could not be reached for comment.

Neff, whose son, Andrew, is a pitcher for UC, has ties to college coaches across the country because of his involvement in amateur baseball, including at Indiana Elite, where he coached at least one team in 2018.

Three sources with ties to UC baseball said Neff, who played college baseball at Louisville, liked to talk about his connections in the game and had a reputation for being brash. The sources asked not to be named because they weren’t authorized to speak for UC baseball.

At the BetMGM sportsbook on April 28, one of Neff’s baseball connections drew immediate attention from investigators: Alabama coach Brad Bohannon.

Investigators haven’t said how the BetMGM sportsbook linked Neff to the coach, but ESPN reported that surveillance video caught the bettor and Bohannon communicating at the time the bet was placed a few hours before the Alabama-LSU game’s 7 p.m. start.

Neff bet on LSU to win.

Fallout spreads quickly to UC baseball

How would the sportsbook’s surveillance cameras pick up communication between Neff and Bohannon? Investigators aren’t saying, but one possibility is Neff’s cell phone.

Cameras at sportsbooks and casinos are both plentiful and powerful. Some may be good enough to zoom in and pick out a phone number or text message on someone’s phone.

“If the government can read your license plate from space, the casinos aren’t too far behind,” said Holden, the Oklahoma State professor. “Casino security is about as good as any security in the world.”

Along with whatever other evidence investigators have gathered, Holden said, one potential red flag related to Neff’s bet is the fact he made the wager at all. He said college baseball is a niche sport for gamblers and sees little betting action until the College World Series.

A Variety Intelligence Platform report drew the same conclusion last year, finding NFL games were by far the most popular among betters. College football ranked high as well, but college baseball didn’t make the list.

Holden said a college baseball game in April, even between two good Division I teams like Alabama and LSU, wouldn’t normally generate big wagers. He said a single bet of $5,000 could move the national betting line for such a game.

“It’s a secondary sport,” Holden said.

© Michael Johnson, AP Alabama baseball players celebrate a a first-inning home run against LSU on April 29, one day after a suspicious bet on the game was placed in Cincinnati.

Before the Alabama-LSU game started, sportsbooks in several states knew there was a problem. At least some sportsbooks outside Cincinnati had also noticed suspicious wagers, Holt said, but investigators haven’t said whether those bets are connected in any way to Neff.

Because of those worries, regulators in Ohio and Indiana immediately suspended betting on the game.

Another worry for the sportsbooks was that Bohannon, who by game time investigators had connected to Neff, still was coaching Alabama.

“The individual who could be manipulating the situation was still there,” Holt said.

Shortly before the game, Alabama scratched its scheduled starting pitcher, Luke Holman, who had the best ERA on the team and was tied for the team lead in wins. He was replaced by Hagan Banks, who ESPN said had not started a game since mid-March. No athletes for either team have been connected to gambling.

LSU, the betting favorite heading into the game, beat Alabama 8-6.

Fallout was swift. Less than a week after the game, on May 4, Alabama fired Bohannon, concluding he had violated “the standards, duties and responsibilities” of a university employee.

Days later, UC began its own internal investigation. On May 17, the university fired hitting coach Kyle Sprague and Director of Baseball Operations Andy Nagel because of “potential NCAA infractions.”

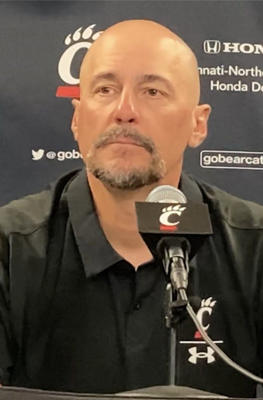

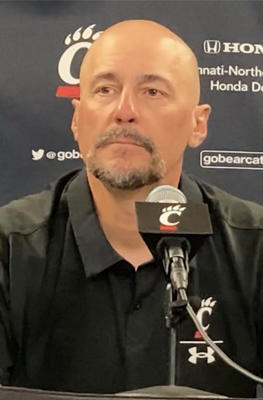

© The Enquirer/Scott Springer Cincinnati Bearcats head baseball coach Scott Googins resigned at the end of his sixth season in May. Weeks before, two UC baseball employees were fired because of their connection to a man who placed a bet on college baseball in Cincinnati April 28.

UC’s investigation found no evidence Sprague or Nagel bet on college baseball, sources said, but the university determined they had knowledge of Neff’s activity on April 28 and failed to report it.

Googins, UC’s head coach, resigned in late May at the end of his sixth season with the team.

Can the system keep up with cheaters?

Whether Neff’s bet on April 28 touches any other coaches or programs remains to be seen. Investigators in Ohio and other states are still at work.

“It will take as long as it takes,” Franks said.

But as sports betting continues to grow – Americans wagered $90 billion with U.S. sportsbooks between May 2022 and April 2023 – so will questions about how best to police and regulate a business that’s gone from a pariah to a partner for sports leagues in a few short years.

As things stand today, regulations and oversight vary from state to state because there is no national system in place. Private firms, such as U.S. Integrity, have stepped into the void by sharing information about potential problems among the sportsbooks and leagues that hire them, as they did after Neff placed his bet in Cincinnati.

“The system is working how it’s supposed to work,” Holt said.

He said U.S. Integrity sends out about 15 alerts related to sports betting irregularities every month and roughly half of those result in suspensions, firings or some kind of legal action. As regulators learn the business better, Holt said, they’re getting better at spotting trouble.

Advances in technology are helping, too. The surveillance Neff encountered at BetMGM is just part of the equation.

Monitoring firms can watch betting lines for unusual changes and can check out large or questionable wagers in real time. They gather bits of information and try to piece together the bigger picture: Is this normal, or is there something nefarious going on?

The tools at their disposal include personal information bettors must provide when they sign up for a sportsbook app on their phones, such as social security numbers and financial data. Applicants also must give the sportsbooks permission to track their phone locations to ensure they’re betting in states where it’s legal.

“The second you log into a regulated sports betting app, we know where you are, we know what you’re doing,” Holt said. “We know everything.”

Yet even with so much data at their disposal, Holden said, the vastness of the sports betting world threatens to overwhelm efforts to police it.

Roughly 1 in 5 American adults now bet on sports, according to a 2022 Harris Poll, and 71% of them place a wager at least once a week. That means sportsbooks must keep an eye on about 30 million bettors every week.

Regulators say they showed on April 28 how effective they can be, but Holden worries about what they may be missing.

Technology alone won’t save the day, he said, and he doesn’t think pro and college teams are doing enough to educate athletes, coaches and others about the rules and the risks associated with sports betting.

Less than two weeks after Neff’s bet in Cincinnati, the University of Iowa and Iowa State University announced a total of 41 athletes at those schools were suspected of betting on sports in violation of NCAA rules.

“It’s going to get worse,” Holden said, “before it gets better.”

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: How an explosion of sports betting ensnared one Ohio college baseball team in a gambling scandal