If you’ve seen “The Sting,” you might wonder whether the “Riverside Park in Kansas City” mentioned in the film actually existed. The horse-racing track played an integral role in the epic con perpetrated by Paul Newman’s and Robert Redford’s characters near the end of the movie.

Yes, Riverside Park was a real place, and it operated north of the Missouri River during the 1930s, when “The Sting” was set.

But there was another Riverside racetrack. This one featured cars rather than horses, and it had a much longer — and perhaps even more colorful — history than the horse track.

Reader John Krpan, who attended races at the car track, reached out to What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between the Kansas City Library and The Star, to learn about Riverside:

“Will you write history from 1951 to 1988 about Riverside Race Stadium, a.k.a. Riverside Stadium or Riverside Race Track?”

The first thing to know is you can’t tell the story of the Riverside speedway (not to be confused with the still-operating Lakeside Speedway in Kansas City, Kansas) without telling the story of the Riverside horse track. The car track might never have existed without the horse track. In fact, the city of Riverside might never have existed without it.

Then there are the names. It seems nobody could settle on one — for either of the tracks. In addition to Riverside Park and Riverside Speedway, you’ll find references to Riverside Track, Riverside Racetrack, Riverside Jockey Club and just plain Riverside.

We’ll go with Riverside Stadium, which appeared on souvenir programs and in most newspaper references to the car track, and Riverside Downs, the name that adorned the Jockey Club building, one of the last remnants of the horse track.

Gary Brenner, whose family once owned much of the land in the area, is an expert on both tracks and just about anything else to do with Riverside. He maintains riversidemissourihistory.com, which includes articles, photos, maps and timelines of the area just east of Parkville and a few miles northwest of downtown Kansas City.

He said the Jockey Club building stood until about eight years ago. Now the only reminders of either track are light poles from Riverside Stadium that still stand in the parking lot of the Red X store, another area landmark. The current store was built in 2023, replacing the original operation that dated to 1948.

“The new Red X building is sitting right where the car track was,” Brenner said.

The car track opened in 1951 just east of the old Red X, which sat on the land of the old horse track.

Memories and mayhem

Krpan’s interest in Riverside Stadium dates to his childhood, when he lived in nearby North Kansas City and attended the Missouri School for the Deaf in Fulton. He said he was a regular at Saturday night races on the quarter-mile dirt track from about 1968 to 1974.

“That was a frequent event for deaf friends to all get together and go to that,” he said through a sign language interpreter, describing it as “a really wonderful experience.”

“You almost could be guaranteed to have a wreck at the races. The drivers would fight with each other. The mechanics would fight with each other. It was a pretty wild and crazy Saturday night to tell you the truth.”

Jim Smith, a friend and classmate of Krpan’s, became a regular driver at Riverside, winning several heats in the Stock Car division in the 1970s.

“He is still the best racer, I say,” Krpan said. “He’s my hero.”

Krpan remains a NASCAR fan. In fact, he and his classmates from the School for the Deaf celebrated their 50th reunion at Kansas Speedway’s May 2023 races, and Smith was on hand.

Jim Harkness, who worked at Riverside Stadium for about 20 years, called Smith “one of the nicest guys at the track. … He won quite a few trophies.”

Serving first as Riverside’s track announcer and eventually as its promoter, Harkness was among the track’s many colorful characters. One of his predecessors as track announcer was Fred Broski, the longtime Kansas City TV weathercaster later known for hosting “Bowling for Dollars” in 1970s.

Harkness was — and still is — known as Hoss because his large frame resembled that of Dan Blocker, who played Hoss Cartwright in the 1960s TV show “Bonanza.”

Blocker approved of Harkness’ use of the nickname.

“I even wrote him and got his permission to wear the big ol’ hat,” Harkness said. “He told me that he would be Hollywood Hoss and I could be Riverside Hoss.”

True to his nickname, Harkness once tangled with three men who didn’t like that he announced a race had ended in a dead heat, even though he had nothing to do with the decision. “At that time, I was the only one they could get to.”

The three approached him in the parking lot after the races and demanded retribution. A tussle ensued, and one of them stabbed Harkness, who described his wound as “not too bad.”

“I think it took about 30 stitches to close me up. … I did some damage to them.”

Damage was a recurring theme at Riverside, which was a quarter-mile dirt track for most of its existence. The tight quarters and banked curves led to regular wrecks. In one 35-lap, 24-car race in 1969, five cars flipped in four crashes, including one triple flip.

“I remember going with my dad,” Brenner said. “I remember cars flying out of the stadium. I think secretly that’s what everybody went to go see.”

With top speeds of no more than 70 mph, injuries tended to be less severe than at bigger tracks with higher speeds. In fact, there is no record of Riverside having a fatal accident in its 37-year history.

Racing included modified stock cars, street stocks, late model, sportsmen, midget cars and even jalopies early on.

As if those races didn’t create enough mayhem, there were also popular races employing the track’s figure-eight configuration. Those competitions resembled demolition derbies, the beat-up cars racing while trying to avoid hitting each other at the crossing.

Inauspicious start

Like the horse track, Riverside Stadium predated the city of Riverside. But only by three weeks — it was incorporated June 21, 1951, and the car track’s opening night was May 29.

That night, a parachutist jumping from 5,000 feet missed the stadium and suffered injuries when he landed in a pasture. About 4,200 people watched Joie Chitwood’s Thrill Show, an exhibition of daredevil driving.

Three weeks later, about 6,000 showed up for a big-time heavyweight fight between contender Rex Layne and Henry Hall. The fans went home drenched when heavy rain hit the area, and the fight was postponed. It was moved to Municipal Auditorium, where Layne beat Hall by decision on June 21. Another three weeks later, Layne lost to the legendary Rocky Marciano at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

By that time, the nonstop rain had produced the historic flood of 1951, and the new Riverside Stadium went underwater. It was closed for more than two months and underwent $60,000 in repairs before racing returned Aug. 31.

At that time, the track was a half-mile oval with seating for 12,000, but within three years it was reduced to a quarter-mile. Seating eventually was 3,000.

Riverside Stadium also held a few professional wrestling matches in the early years, but its biggest event likely occurred when the Hadacol Caravan medicine show drew a crowd The Star estimated between 15,000 and 18,000 on Sept. 13, 1951. Admission was a box top from Hadacol, a supposed vitamin supplement that contained 12% alcohol. Entertainer Dick Haymes and former boxer Jack Dempsey were on hand.

Auto racing is what Riverside is remembered for, however, and it produced not only memorable action but also high-quality drivers. Most were from the Kansas City area, Riverside in particular.

“I remember as a kid driving through the neighborhood seeing stock cars out in the driveway and guys out there working on them trying to get ready for Saturday night,” Brenner said.

The top driver probably was Greg Weld of Kansas City, who went on to win the 1967 USAC National Sprint Car title and drive in the 1970 Indianapolis 500. Texan Jud Larson drove at Riverside before claiming an eighth-place finish at Indy in 1958.

Ed Young owned Riverside for nearly all of its history. He bought it in 1953 when, as owner of the Red X, he was tired of the track’s parking and noise problems. So he took matters into his own hands.

“There really wasn’t any other reason,” Young, who later became Riverside’s mayor, told The Star in 1984. “I’m not a race person. I didn’t start out a race fan. Whatever I made on it I’d spend on a party and make improvements.”

Young owned the property until its demise in 1988, by which time Riverside Stadium had fallen into disrepair.

“It needed to be closed,” Hoss Harkness said.

“I just remember it was past ready,” Brenner said. “It was to the point where it needed to be all bulldozed down and rebuilt.”

Pendergast’s track

OK, back to the horse track.

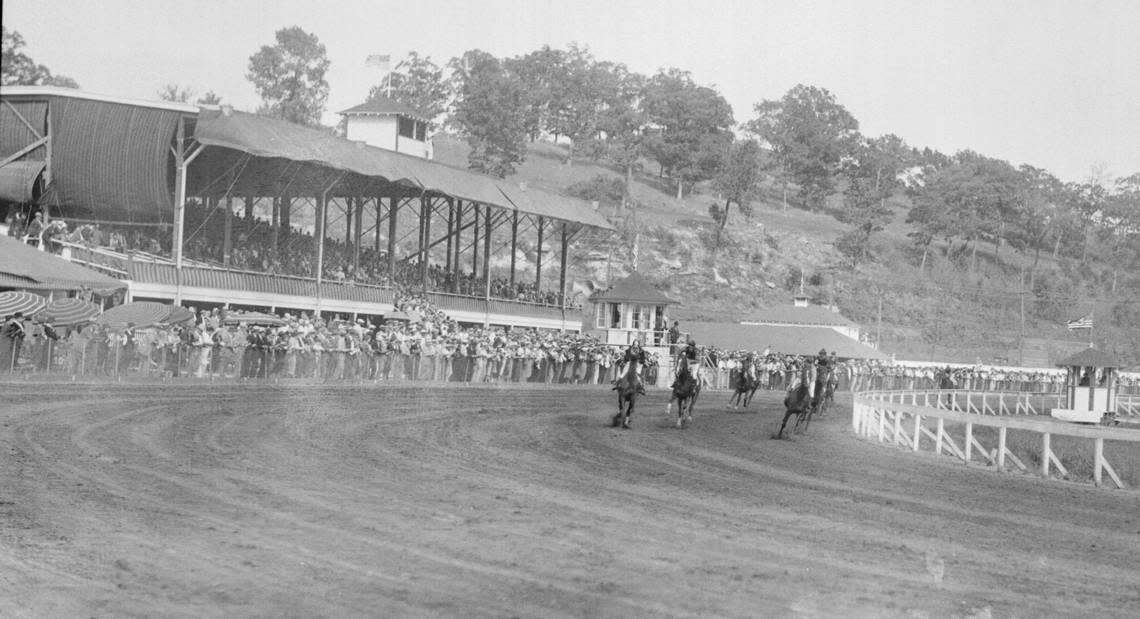

Opened in 1928, it was commonly referred to as Pendergast’s track. Kansas City political boss Tom Pendergast’s name wasn’t on any of the paperwork, but everyone knew he was the man behind the operation.

How else could they have gotten away with it?

After all, parimutuel betting wasn’t legal in Missouri, and no horse track can survive without fans betting on races. Riverside Downs got around that by offering “donation” gambling. Fans made contributions supposedly to help improve the thoroughbreds in each race and collected refunds if their chosen steeds showed improvement by running faster than all their competition. They even got refunds if horses showed slightly less improvement by finishing second or third.

None of the revenue went to government entities, so Pendergast no doubt made a tidy profit. But in addition to owning the track, Pendergast also owned a stable of horses that ran at Riverside and elsewhere. And he bet on the racing. A lot.

Estimates place his horse betting as high as $1 million a year, with most of that resulting in losses. Pendergast also likely spent time and money at the nearby Cuban Gardens, a night club and gambling casino operated by mob boss Johnny Lazia (until Lazia’s tax-evasion conviction in 1934 and his ensuing murder).

Some folks were outraged by the Riverside gambling scheme, but it lasted until 1937, when Pendergast’s power was waning.

Even those opposed to Riverside’s gambling couldn’t deny its positive effect. Pendergast’s track led to widened roads, new roads and even the Fairfax Bridge, which opened in 1935. It also produced a name for the area.

“Riverside got its name from Pendergast,” Brenner said. “Before the horse track, it was just known as east of Parkville or Brenner Ridge. And he’s the one that said it had to have a name because he had to put it on the ads. He’s the one that said, ‘Let’s call it Riverside.’”

Ultimately, Riverside Downs provided a lot of entertainment for a lot of people.

Thousands attended the seven to nine races daily during monthlong spring and fall meetings, highlighted by a record 18,000 on Memorial Day 1933. A horse named Jim Dandy, who had pulled off one of the greatest upsets in thoroughbred racing history a few years earlier by beating the legendary Gallant Fox at 100-1 odds, claimed Riverside’s Memorial Day Handicap despite having the longest odds in a seven-horse field.

Jim Dandy eventually retired after just seven wins in 141 starts, then the rock group Black Oak Arkansas paid homage to him with a 1973 song called “Jim Dandy.”

But even Jim Dandy wasn’t Riverside Downs’ most memorable horse. That would be Lucky Dan.

He was immortalized by Doyle Lonnegan’s line in “The Sting”: “I’m putting half a million dollars on Lucky Dan to win, third race at Riverside Park.”

Unfortunately for Lonnegan, Lucky Dan placed second in the third race at Riverside. The Irish mobster was out $500,000 (about $11.3 million today), but it gave the movie a satisfying conclusion.

It also sparked Brenner’s interest in Riverside history.

“The movie ‘The Sting’ is really what got me interested in this,” he said. “I couldn’t believe anybody would mention Riverside.

“I got into all hands and feet, head deep.”

For the record, a horse named Lucky Dan did race in the 1930s, finishing his career with 21 wins in 101 starts.

Lucky Dan ran six times at Riverside in 1936, the year “The Sting” was set.

He won once and finished second twice.

But he never ran in the third race.