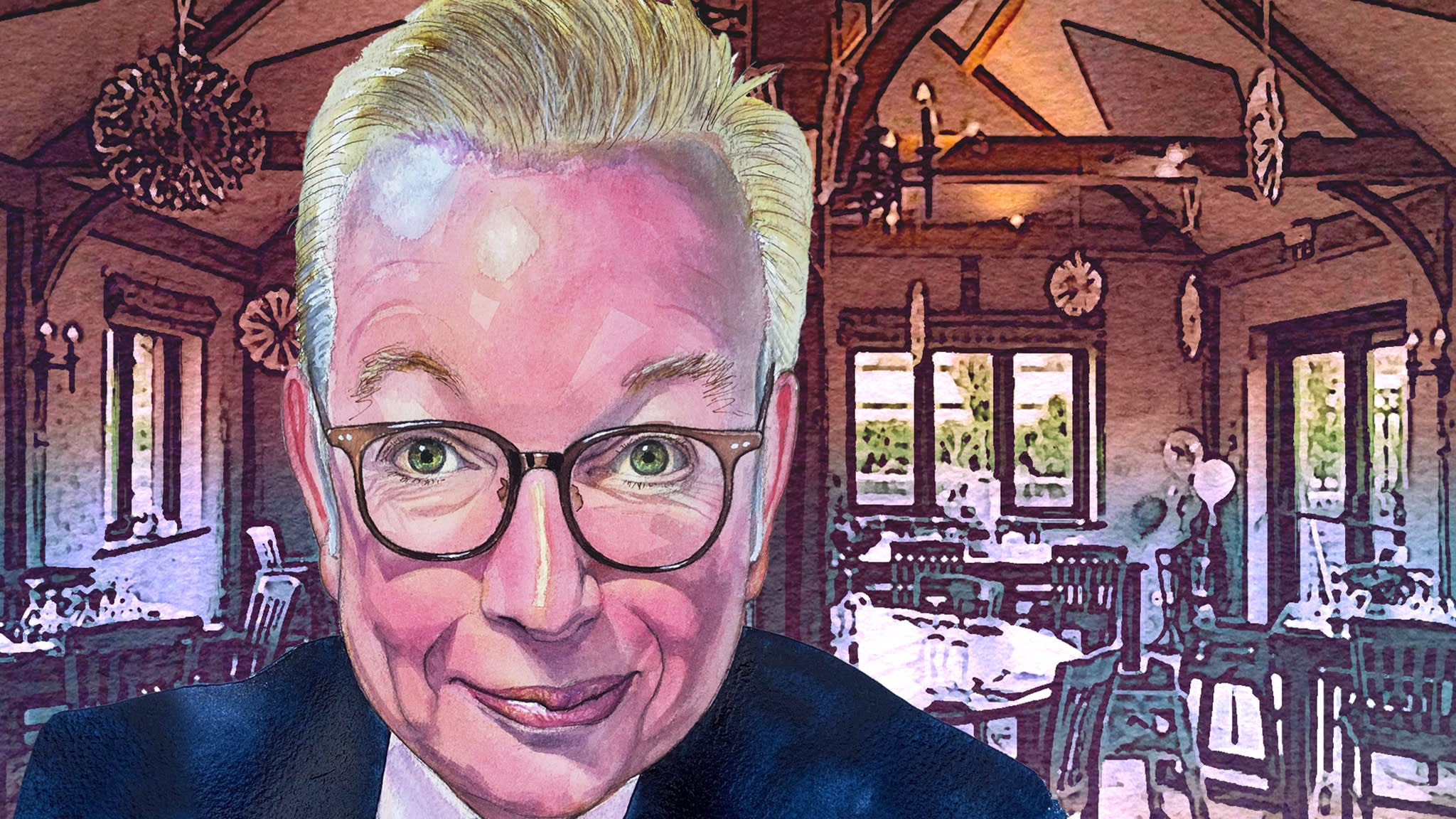

As Michael Gove strolls into The Half Moon pub in the heart of his affluent Surrey constituency, nearly every customer looks up to goggle at their local celebrity. In his customarily effusive manner, the veteran former Conservative minister — and perma party plotter — greets them all individually. He is notably smarter than the rest of the clientele, in his blue politician’s suit, Union Flag cufflinks and Hermès tie. The 55-year-old has not been a British government minister for three months, yet he is still very much dressing — and acting — the part.

We are meeting three weeks into Liz Truss’s turbulent premiership. Barely a day after our encounter, Gove formally recast himself as her chief Conservative critic, leading the rebellion that led to the prime minister scrapping plans to cut the top 45p rate of tax. As we settle into a corner table, Gove wastes no time in setting out his critique of her position: “I don’t think it was an optimal start for a new prime minister.”

He was offended, he says, not by Truss’s decision to slash taxes, but to do so mainly for the wealthiest. “If you really wanted a tax cut that helped the poorest and those most in need, you do a different tax cut,” he says. “I completely understand the impulse, the rationale, the thinking behind what’s been done, but my only strong advice to the team would be to acknowledge fault without retreating from your essential worldview.” A few days after our lunch, Truss does just that — while suggesting that she would still like to see the top rate of tax slashed in the future.

Gove has been manoeuvring at the heart of British politics for more than a decade and flirting with rebellion for many a year. A leading minister in David Cameron’s government before they fell out, he was one of the most influential supporters of Brexit, and a key minister under Boris Johnson — before they too fell out, in this case for the second time.

The prime minister’s allies view Gove’s latest rebellion as revenge for Truss’s decision not to offer him another ministerial posting — a charge he denies. “The approach Liz has taken to her government and her team makes perfect sense. She wants to have a team 100 per cent aligned with everything that she’s doing,” he smiles. “I can understand why she wouldn’t want aged relics from the past, like me, cluttering up the Cabinet room.”

The barman returns to take our order. Gove doesn’t drink before 6pm, but when I moot the prospect of a lunchtime beer, a spring is uncoiled. Gove leaps up to tour the pumps and taps. Stalking the bar, he recommends Summer Lightning — an award-winning ale from Salisbury — for me, while he opts for a pint of Diet Coke.

So why did the UK’s “mini” Budget trigger such a negative reaction, when most of the measures had been announced during this summer’s Tory leadership contest? “Having already baked in tax changes for which there was an understanding, it had an element of risk which was skewed towards the wealthier. There was a doubling-down both on risk and on the opposite of redistribution.” He acknowledges that “daring audacity is required in politics”, but this economic moment is “really not a time for gambling”.

There is no recklessness in Gove’s lunch order. We opt for the pub favourites of oxtail broth to begin, but diverge on the main courses. Gove goes for the seared calves’ liver with treacle bacon; I pick the house beef burger with smoked Cheddar and extra crispy fries. He asks if the barman could “kindly” pour another Diet Coke, as I nurse the beer.

Gove’s objection to cutting taxes for the wealthiest is, he says, based on Tory principles. “The essence of being Conservative is that you should do everything possible to avoid taking risks with the economy and with people’s jobs and with mortgage rates.” After the disastrous “mini” Budget, the pound sank to its lowest-ever level against the dollar, government borrowing costs soared, hundreds of mortgage products across the UK were withdrawn, and the nation braced for interest rates to soar above five per cent.

Such recklessness may never be forgiven. “It’s all very well to say fortune favours the brave, but there are some moments where you are unlikely to follow someone who is exceptionally brave because they are charging towards the guns without necessarily the artillery support that you would expect.”

Gove is affable and polite, but his radical policy zeal has made him a divisive figure. He honed a reputation as one of the Tory party’s more effective politicians thanks to his role in the modernisation project that began under Cameron’s leadership in 2005, the year he first entered parliament after a successful career as a columnist and editor on The Times.

He is scathing about where conservatism has gone in the past few months. “There is a strain of free-market economics, liberal libertarian thinking that supports what’s going on [with Truss]. You have columnists and commentators who support it, invoking Hayek and Friedman, but Hayek famously wrote an essay ‘Why I Am Not a Conservative’.

“The Conservative tradition is not to be a pure economic utilitarian,” he continues, casting back to the 19th-century debate between Manchester Liberals and the Tory governments of Benjamin Disraeli and Lord Salisbury. “You obviously don’t try to defy economic gravity, but you recognise that there is a role for government and for values other than those of the market, and that is proper conservatism.”

Indeed, Gove feels compelled to defend all of the party’s recent leaders and chancellors from the attacks by libertarian Tories. “It’s not as though we weren’t thinking about growth for the last 12 years . . . They shouldn’t attempt to edit the past to suggest that David [Cameron] and George [Osborne], Theresa [May] and Philip [Hammond], Boris and Rishi [Sunak] were somehow members of a Marxist cell.”

As the oxtail soup arrives — the meat is succulent, swimming in tomato, with a side of soft sourdough — we flip back to his earlier career. During his time in opposition (he was first voted into parliament when Tony Blair won his third election) and later as education secretary, he was part of a movement under which the Tory leadership embraced same-sex marriage and took steps to select more diverse MPs.

But for Gove, modernisation was about “much more” than social issues. “One of the things that David did was to say we had to a) move away from unfunded tax cut promises, b) not having an approach towards the public services that was about helping people to opt out [from state support] and c) move away from the idea that the answer in education was grammar schools and more selection.” In some form or another, every one of those has been junked by Truss. He sighs when I point this out.

Gove’s time as education secretary was his most radical — and most controversial. He sought to raise attainment with the academies and free schools programme, removing them from what he saw as statist local authority control, ripping up the curriculum to focus on more traditional subjects and battling with the teaching unions. A scheme to rebuild and revamp schools across the country backfired. “I announced something too quickly because I was anxious to show that change was coming. I was impatient with the way that things had operated beforehand. . . It was done in both an insensitive and a hurried way.” The lesson, according to Gove, is to “honestly acknowledge fault relatively early on” and gain “permission to reset”.

Education reform seemed set to be Gove’s legacy — until Brexit. During the 2016 referendum, he teamed up with his former aide Dominic Cummings to argue the case for Leave. Gove admits his infamous quip that the country had “had enough of experts” will probably be on his tombstone. He insists he did not want the referendum, finding himself opposing his old political friend Cameron, who as prime minister made the case for Remain.

With the UK continuing to struggle with the economic impact of leaving the single market and customs union, and an unclear vision of how the country might take advantage of its status outside the bloc, does he harbour regrets? “I ask myself all the time, ‘was it the right thing to do?” he says. “I still think that it was right, but that doesn’t mean that a choice as momentous as that doesn’t require you, from time to time, to think, ‘What are the downsides?’ ‘Has it turned out in the way that you might have imagined?’ ‘What lessons can you learn from it?’”

Our main courses arrive. Gove tucks into his calves’ liver, deep in gravy, while I topple half of my burger, cooked to medium-rare perfection. The case for Brexit not yet made, Gove continues. “I think that Dom Cummings has made it clear firstly, if you think it was a mistake, you have to imagine what it would be like if we were still in the EU, and what that would mean — not just today, Friday, but in the future. . . You’ve also got to look at things both in terms of the path not taken, but also in terms of the lessons you learn as a result of those decisions having been taken.”

But what benefits can he ascribe to the decision? He cites the “speed and nature” of the UK’s vaccine rollout — while technically the UK could have overseen its own vaccination programme as a full member of the EU, that would never have been likely. For him, this is what matters. “Brexit is a good thing in itself, in that it is the reassertion of democratic control over politicians and the stripping-away of the capacity for politicians to make excuses for their own failures. But it all depends on how it’s used, and the policy consequences that come from it.”

Like Cummings, Gove is hopeful that Brexit Britain can respond to emerging technologies and threats more adeptly and rapidly. “It’s not so much about ripping up existing rules, though there are obviously some that can be amended and/or ditched. It’s more about how we look at everything from the future of life sciences to the future of AI, to the future of financial services. Are we going to regulate in a particular way that is more pro-science or pro-enterprise?”

Brexit may be the only area where Gove has kind words for the new prime minister. “She is right that there are opportunities that we could have taken that we haven’t, and she is right to be impatient with the inertia within some government departments and some regulators. But, as ever, the judgment is you can’t be impatient with everybody all the time. You’ve got to prioritise.”

With the lunch plates and glasses cleared away, Gove has a little time left for coffee — a double espresso for him, a white Americano for me. We shift into reflective territory. What did Gove regret the most from his 12 years as a minister? “Not spending enough time with my family,” he replies — he got divorced from his wife of 20 years, newspaper columnist Sarah Vine in January this year, after she stated that his “only mistress was politics”.

What about his biggest mistake in office? He looks around the pub, making awkward noises while seeking to alight on the right answer. Eventually, he concludes it was his early decision to cancel the schools refurbishment programme. He also wished he had had more time at the Ministry of Justice (Theresa May sacked him as justice secretary after the Brexit referendum). The answer does not feel wholly convincing.

Gove’s most painful legacy, however, is with Boris Johnson. The pair met at Oxford, where he ran the future prime minister’s campaign to be president of the university’s Union debating society. They rose as Tory-leaning journalists in the 1990s before turning to politics. Both backed Brexit in the 2016 referendum, but their relationship came asunder when Gove publicly announced that Johnson was not up to the job of being prime minister, sinking his leadership campaign.

With hindsight, does he regret turning on him? “I think I probably shouldn’t have,” he says. “What I said reflected particular circumstances at a particular time. I like Boris, I admire Boris, and things ended badly and unhappily, but I wish it worked out in a different way . . . there were all sorts of lessons for me to learn from what happened in 2016.”

When Johnson became prime minister three years ago, he kept Gove in his government, first as his chief fixer in the Cabinet Office, then as his “levelling up” secretary to oversee efforts to tackle regional inequality following the 2019 election. The pair were united in seeing the Brexit referendum and ensuing election as evidence that the country wanted “a different sort of conservatism” chiefly focused on addressing inequality of opportunity.

According to Gove, the Brexit vote revealed that his party had become “a little bit too southern, a little bit too professional, more Waitrose than Lidl, as it were”, he says, in reference to two of Britain’s leading supermarkets. “That maybe the next part of the. . . modernisation, or relevance, or Conservative adaptation, was to become a party which had a much broader basis across class and geography.” Gove oversaw the release of a policy document that sought to deliver on the “levelling up” vision, but the collapse of the Johnson government meant it never came to fruition.

The Johnson-Gove working relationship finally came to an end after Gove visited Downing Street the day before the prime minister quit, to tell him to go. Johnson saw it as another betrayal and abruptly fired Gove as one of his final acts in Number 10. “I’m sad about the way that it all ended,” Gove sighs. “But I think you’ve got to accept, with as much good grace as you can muster, that if you’ve been a minister for as long as I have that when it ends, it ends”. For a second, his confidence seems to waver. “As you can tell . . . it’s still painful to dwell on it because it was a very difficult time.”

With the pub finally empty, Gove scoops up his battered briefcase to resume his constituency work. With little prospect of returning to ministerial duties, he will probably go back to writing newspaper columns. He will finish a long-delayed biography of Viscount Bolingbroke, a leader of the Tories under Queen Anne, and is eyeing up a return to radio broadcasting, something he has not done since his early years as a journalist.

Gove will not be leaving parliament either, so if the call came from Truss, or a successor, would he return to the limelight? “I don’t think you can say never.”

Sebastian Payne is the FT’s Whitehall editor

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter