While hiking along the Angostura Interpretive Trail — located seven kilometers north of Lake Chapala — I came upon a flat rock about the size and height of a low table.

Incised upon it was a simple design: a circle divided into four parts by a cross, with a small circle in each section. Outside the design, as if by way of signature, there was a simple sketch of a jaguar’s head.

I had never seen a petroglyph quite like this. Getting home, I sent a photo of the rock to archaeologist Joseph Mountjoy, who has spent much of his life discovering, cataloging, and interpreting petroglyphs in western Mexico. “It could be an abbreviated patolli,” replied Dr. Mountjoy. And with this message, I was launched into the intriguing story of the pre-Columbian patolli.

Playing with poisonous beans

The word patolli, Mountjoy explained to me, is Nahuatl for an ancient form of what we call board games, in which markers are moved along a track, which might be scratched in the ground or painted on a portable mat — and only rarely carved into the surface of a flat rock.

The number of spaces the markers move depends on the throw of objects that served the same purpose as dice. In many cases, they were dark-red beans — also called “patolli” — with a white hole on one side. These were probably poisonous mescal beans (Sophora secundiflora).

Just as in modern board games, a throw of the beans might land a player’s token on a square where they lose their turn, get an extra turn, or — if they are unlucky — get sent back to the starting space.

Gambling and drinking

Perhaps the earliest account of how the game was played was written by Spanish historian Fray Diego Durán. It may have been transcribed from a native manuscript written shortly after the Spanish conquest:

“On this mat was painted a large X, which reached from corner to corner to corner. Within the arms of the X certain lines were marked or striped with liquid rubber… Twelve pebbles were used in these squares: six red and six blue. These pebbles were divided among those who played, each given his share.”

“If two played, which was the usual form, each took six pebbles and when many played, one played for all, [the others] abiding by his luck, just as the Spaniards play games of chance betting on whom [they hope to be] the winner. The same was done here. [Bets were made] on the one who best handled the dice. These were black beans, five or six, depending upon how one wanted to play. On each bean was a small space painted with the number of the squares which it could advance at each play.”

Patolli, Mountjoy told me, was played by both the rich and the poor, and the playing of the game was apparently a very lively event, filled with excitement.

“The only ethnographic evidence that we have about what went on,” said Mountjoy, “is in respect to the Aztecs. There would tend to be two players playing on the board. Each one had his team and the team would be betting. Based on what we know about Mesoamerican betting, they could bet anything and everything: precious stones, land, women, children, clothes. And they drank pulque while they played. So it sounds a bit like Las Vegas, where you might see people at the roulette wheel with their friends behind them, rooting them on and drinking their cocktails. This was the poker of those times.”

This image is consistent with the findings of American ethnographer Stewart Culin who published “Games of the North American Indians” in 1907. “Culin’s work,” said Mountjoy, “indicates that Indigenous people truly liked to play games, lots and lots of them.”

11,000 petroglyphs but only one patolli

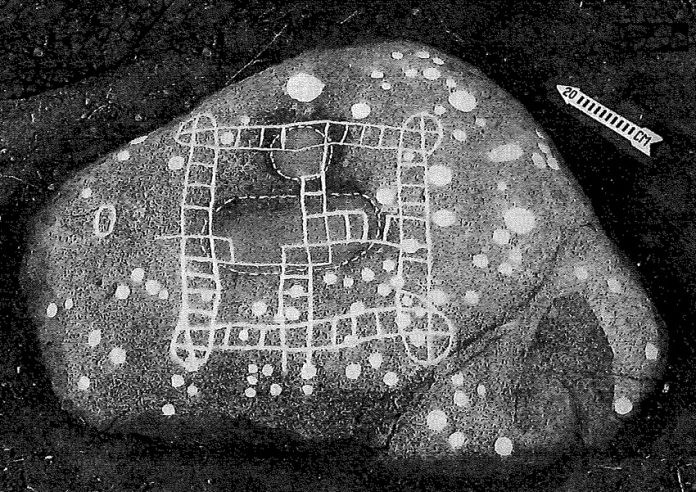

Joseph Mountjoy had no knowledge of patollis until he and his team found one incised on a horizontal rock in Jalisco’s Tomatlán Valley in 1977.

“When I saw it, I said ‘This is a strange-looking thing,’” he told me. “It was all the more remarkable because we had already found 11,000 petroglyphs in the Tomatlán Valley… but only one patolli! So I started digging into the subject of patollis. I learned, for example, that in the 1940s an anthropologist had described Tarascans playing patolli on a board. It turned out you could take the rules that the Tarascans were following and use them to play the game on the patolli design we found in Tomatlán. This was impressive.”

While researching the Tomatlán area, adds Mountjoy, “we also found several odd ceramic pieces. One is shaped exactly like a Hershey’s Kiss and the other is a pottery disk somewhat resembling modern checkers, with a gouged pit on one side and a cross incised on the opposite face. It seems possible that they were using one of these as the marker and the other as the die. The latter resembles the bone dice used by numerous native American groups.”

“For a long time,” Mountjoy told me, “the literature suggested that Indians from India had contacted the American civilizations and had introduced the game of Parcheesi to them, which became known as patolli. But they were just a little bit off. Recent research into this topic has proven that it was the patolli game of Mesoamerica that went to India, and not vice versa. The game doesn’t appear in India until the 1500s or 1600s.”

Patolli today

“Are people in Mexico still playing these games somewhere?” I asked Dr. Mountjoy.

“I was in Mazatlán not long ago,” he replied, “for a conference on patollis, and while I was there discussing this, somebody told me that people were still playing a version of the patolli up in the mountains east of Mazatlán. They may have been incising the design on the ground, and they were using bottle caps on the boards.”

If you’d like to try your hand at the Mesoamerican game of patolli, there’s no need to travel all the way to Mazatlán. Thanks to the kind folks at the Otago Museum in New Zealand, of all places, you can download and print out your own patolli board, complete with directions on how to play (though without any pulque). I just hope these New Zealanders’ next project will give me directions for playing on the abbreviated patolli I found near Lake Chapala.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.